The EU Votes for Continuity

The new European Parliament (EP) will see an estimated, and limited, 16-seat gain for parties to the right of the center, with the two main far-right political families, European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID), getting 13 of those seats in a legislature with 720. The centrist majority of the European People’s Party (EPP), Socialists & Democrats (S&D), and liberal Renew Europe looks set to retain its standing with about 400 seats (see Table 1). It, therefore, will continue to hold the balance of power, despite voters’ suffering from the worst cost of living crisis in a generation. The result means no major shift in some key policy areas. European environmental and carbon pricing policies will stay in place, recently enacted reform of EU procedures for processing asylum seekers will remain unchanged, and the bloc’s strong support for Ukraine will continue.

| Political group | Seats |

| European People's Party | 190 (+14) |

| Socialists and Democrats | 136 (-3) |

| Renew Europe | 80 (-22) |

| European Conservatives and Reformists | 76 (+7) |

| Identity and Democracy Group | 58 (+9) |

| Greens/European Free Alliance | 52 (-19) |

| The Left | 39 (+2) |

| Unaffiliated | 45 (-17) |

| Others (newly elected members not allied to any political group in the outgoing parliament) | 44 (n/a) |

| Total of seats | 720 |

| Source: European Parliament, https://results.elections.europa.eu/ |

Although no far-right surge engulfed the EU, parties on this part of the political spectrum did well in the EU’s two most powerful countries, Germany and France. Both are today characterized by weak incumbent governments, but the far right has never been in (or near) power in either. That allowed the populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) to successfully campaign as outsiders who can bring change. Elsewhere, in states with experience of far-right national governments, the appeal of such parties was far weaker.

In Poland, centrist Prime Minister Donald Tusk defeated the far-right Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS), and in Slovakia, the liberal Progresívne Slovensko (PS) beat the ruling nationalist Sociálna Demokracia (SMER). More importantly, a new center-right opposition party in Hungary got approximately 30% of the vote, dealing the first domestic political challenge to authoritarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in over a decade.

In Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli di Italia (FdI) did well, but success came from cannibalizing her coalition partner, Lega, which is even further to the right. The result could undermine that party’s leadership. Meloni, however, solidified political stability in Rome and put herself in a better position to leverage Italian influence at the European level in the next five years.

With the EP election over, the political impetus shifts from fighting a campaign to ensuring that EU institutions continue to function smoothly. The most immediate priority in this regard is cementing a simple parliamentary majority to confirm the next European Commission president. This is almost certain to be a reelected Ursula von der Leyen, whose EPP performed well in the election and remains the largest group in the parliament. Her nationality is another factor in her favor. Denying her a second term would require Germany to receive political compensation, likely in the form of the European Central Bank presidency, which will be available in 2027. But few governments that use the euro are likely to be willing to pay that price. French President Emmanuel Macron will be especially sensitive to cede the position to a German in a year that coincides with his country’s next presidential election. Agreeing now to a second von der Leyen term is a much more politically palatable strategy. She is even likely to garner support from the left-leaning Greens/European Free Alliance parliamentary grouping, which was battered in the vote and now seeks another way to wield influence over Commission policies.

Still, the vote may be deceptively close as individual members of the European Parliament (MEPs) chose to personally signal their opposition to von der Leyen. Their “no” vote, however, will have no political impact—unless the secret ballot succumbs to an “accident”. There is a chance that too many individual MEPs register their opposition and deny von der Leyen a second term, despite their party family’s instructions not to do so. Should that happen, the EU would likely usher in a months-long period of political paralysis that would tear further into support for mainstream parties.

Whether or not there is a tussle over the Commission president, the incoming EP will no longer have natural majorities on most political issues. Leaders of centrist political families will need to create whip operations to enforce party discipline more strictly on often-unruly members. This will have its advantages by helping turn the parliament into a more confrontational body in which decisions are made through open votes, not back-room deals among the dominant centrist political families.

Plus C’est la Même Chose

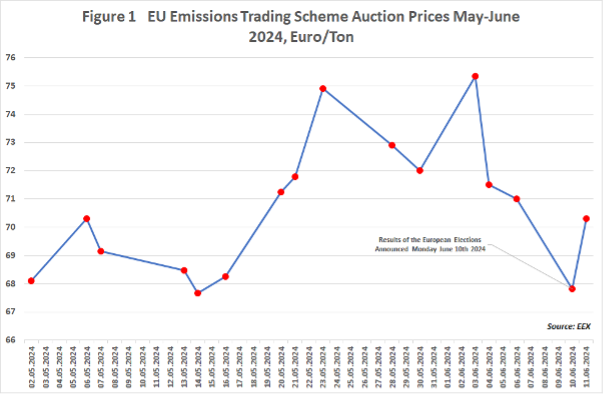

The greater transparency is unlikely, however, to affect significant policy change. The main components of the EU Green Deal are not threatened, especially since the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is set in in bloc law, and the far right, which wants to curtail environmental regulation, lacks the votes to rescind the legislation. Confidence in the ETS is reflected in the emissions price, which recovered from a fall immediately after the EP election results became clear (see Figure 1).

For Ukraine, the outcome of the French parliamentary election will have a greater bearing than the EP vote. Should Marine Le Pen and her far-right National Rally emerge with a majority in Paris, she could oppose French participation in further EU support for Kyiv. Her influence may even extend to a pullback by Macron, who now leads the charge for more Ukrainian assistance. The opposite is true, however, for Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who suffered a setback in the EP election results. He may now rethink the eagerness with which he has stymied EU support to Ukraine until now. Overall, however, a clear majority in the EP remains strongly pro-Ukraine, and that is likely to ensure future assistance for the country.

Lastly, on immigration, the election is unlikely to bring about any tightening of the rules. These are still set mainly by member states, so any changes may arise in Paris before Brussels. The EU did establish earlier this year a bloc-wide procedural framework for immigration, but it took eight years of negotiations to reach agreement. There is limited appetite for amending it.

In the end, EU voters cast an aggregate vote for continuity. Brussels will, therefore, operate much like before. Any real impact will be in the member states, with the first reverberations already apparent in France.