Responsible Reporting in an Age of Irresponsible Information

Photo Credit: Hadrian / Shutterstock

In Brief: Disinformation and misinformation seem to be everywhere. They are often spread by foreign actors like the Russian government who aim to stoke tensions within the United States. Other state or non-state actors may already be starting to copy these tactics. The problem of disinformation is exacerbated by two deeper and longer-standing crises within the American media system: a crisis of business model and a crisis of norms.

Though issues of disinformation are not new, their appearance in new forms of weaponized information and social media call for new best practices within media organizations. This brief suggests some simple solutions to help journalists and editors avoid playing an unintentional role in information warfare and to increase trust in journalism. The recommendations fall into three categories: how to detect disinformation; how to increase literacy about foreign interference; how to anticipate future problems today.

Current assessments of reporting on Russian interference in Western democratic institutions fall into two diametrically opposed camps: the pessimists and the optimists. Optimists point to increased subscriptions to publications like The New York Times and vigorous reporting on complicated stories like Russian interference in the U.S. election. They praise journalists for careful investigative work that has often anticipated developments in the Mueller investigation or unearthed information in the public interest. Pessimists point to media organizations that unintentionally act as pawns in an international chess game of disinformation by amplifying extreme and/ or fictional figures and news. They worry that media outlets are failing to explain the threats to American democracy and are chasing traffic over truth.

Though they may seem contradictory, both assessments ring true. But strong investigative reporting by major outlets does not absolve them of the responsibility to address the pessimists’ valid concerns. We find ourselves confronted with a “firehose of falsehood” from governments like Putin’s Russia.[1] Any overall reaction will involve interlocking responses from government, educators, civil society, and journalists. This is not simply a reaction to Russia, but rather an opportunity to strengthen democratic resilience. Russian tactics to spread disinformation and exacerbate tensions within the United States may soon be copied by other state or non-state actors. Though these problems are not new, their appearance in new forms of weaponized information and social media call for new best practices that media organizations might enact.

At a time when there seems to be more information (and more disinformation) than ever, independent and vigorous reporting remains a vital pillar of democratic society. The cautionary tale of restricted media spaces in countries like Russia reminds us that disinformation is likelier to take hold when citizens have little or no access to independent sources of news.[2] An open media system is not to be taken for granted. Without a wide variety of independent media outlets, there is a vacuum, which disinformation can fill.

Although the Trump presidency seems to have revitalized media outlets and increased audiences on television news channels, these numbers obscure two deeper and longer-standing crises within the U.S. media system: a crisis of business model and a crisis of norms.

Less Money, New Norms

The business model crisis has been building over the last few decades, as television removed ad revenue from newspapers and then the Internet swiftly cannibalized ad revenue from both television and newspapers. Over the last few years, Google and Facebook have carved out an increasingly dominant share of ad revenue. 73 percent of all digital advertising in the United States went to this duopoly in Q2 of 2017, up from 63 percent in Q2 of 2015. The two also accounted for 83 percent of all growth in digital advertising revenue.[3] Although Facebook is now restructuring its algorithms to downplay news articles in favor of interactions between users, it is too soon to tell how this will affect news organizations.

The business model crisis makes news organizations more susceptible to disinformation.

What we do know is that digital advertising provides far less revenue to news organizations than traditional print and TV ads — with serious consequences. News organizations, particularly local outfits, have shed reporters at a precipitous rate. Newspaper publishers employed 455,000 people in the news business in 1990; by early 2017, this had dropped by more than 50 percent to 173,900 employees.[4] Most remaining media organizations and new Internet media companies are firmly based in major metropolitan areas, though even they are struggling to stay in the black.

Media outlets are shifting to new business models, whether relying more on revenue from subscribers, organizing events, or being bought by a billionaire. BuzzFeed has, for example, developed a nine-box model that combines multiple revenue streams from advertising, commerce, and studio development.[5] But there is, as yet, no sure solution. The business model crisis makes news organizations more susceptible to disinformation: outlets chase eyeballs to secure ad dollars; there is a push for quantity of articles over quality; cost-cutting in the newsroom has reduced the number of editors who check copy before it is posted.

Revenue issues have intertwined with the second crisis of norms in journalism. Older journalistic standards like neutrality, balance, or objectivity — what media critic Jay Rosen in 2003 called “the view from nowhere” — developed over the 20th century and seemed so natural that we often forget their relatively recent origins.[6] The rise of social media and online media outlets challenged these older norms in several fundamental ways. Rather than news organizations setting the agendas for readers, organizations increasingly pull their content from social media, writing articles around whatever post, photo, or tweet has just gone viral. Ordinary people can now easily publish on platforms like LinkedIn or on sites like Huffington Post that rely on citizen journalists (though Huffington Post itself has just moved to a more curatorial model).[7] Readers can also push back against journalists in comment sections and on social media. News articles no longer exist in a vacuum without reader responses. This can create vigorous and meaningful debate; it can also give oxygen to extreme views as well as create space for abuse and misuse by bots and trolls.

The current concatenation of these two crises has made journalism particularly vulnerable to foreign attempts to spread disinformation. The systemic issues underlying these two crises deserve urgent attention. No one policy brief can overturn the economics of news or upend the culture of journalism. We recognize the constraints of media organizations and the difficulties of making sweeping changes. However, we can implement immediate incremental shifts to foster more responsible journalism.

Here, we focus on tactics over strategy and on solutions that can be applied tomorrow. We suggest some simple best practices to help journalists and editors to avoid playing an unintentional role in information warfare and to increase trust in journalism. Our recommendations fall into three categories: how to detect disinformation; how to increase literacy about foreign interference; how to anticipate future problems today.

1. How to Detect Disinformation

There are many types of deliberate disinformation. Some are domestic and some are foreign. The two most successful types of coordinated and deliberate foreign disinformation have been weaponized information and fake personae.

Weaponized information includes both leaking information and amplifying (dis)information designed to sow distrust or create discord. Journalists are key to foreign (dis)information campaigns based on leaked or hacked information dumps. These campaigns only succeed if journalists amplify the dumps by reporting on their contents. While some people will pick through the vast amount of information released in a data dump, the vast majority only hear about leaked or hacked information through traditional media organizations’ reporting.

Journalists have of course always relied on leaked information and are well-equipped to assess their sources’ reliability. Yet, new forms of leaks through hacking create new dilemmas. Journalists seize the information disclosed in a hack, but it is harder to assess whether the source is reliable or the hacked information valid when they do not have direct contact with the leakers.

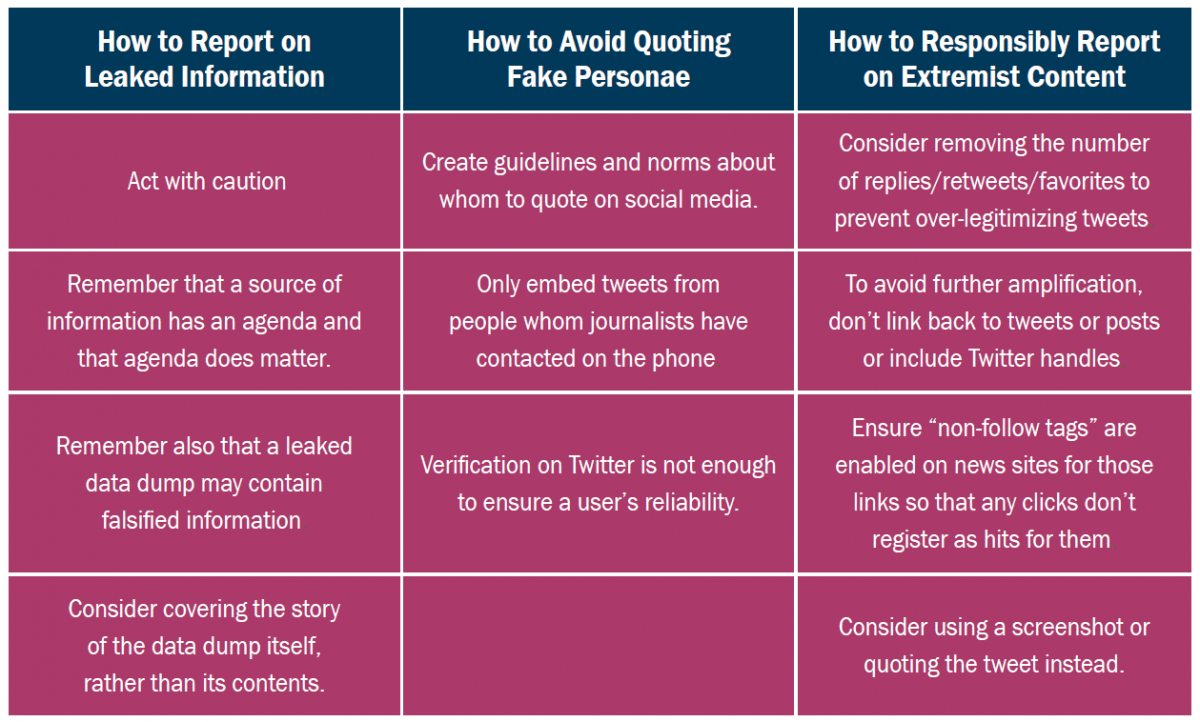

In many ways, journalists would do well to go back to basics with weaponized information. Remember that a source of information has an agenda and that agenda does matter. Journalists are used to dealing with sources who have an axe to grind. We are not asking journalists to stop being journalists. But journalists may be pawns in a bigger chess game. Hacking operations by states or non-state actors can only successfully weaponize information if journalists publicize the contents of the hacks. When journalists report on leaked information posted online by outlets like Wikileaks, it is important to act with extreme caution. Consider whether stories on that type of material deserve the prominence that they received during the 2016 election campaign. Many readers may see stories online, but page one still sets the agenda.

Remember also that a leaked data dump may contain falsified information. Emmanuel Macron’s campaign even deliberately included erroneous information to invalidate any hacks of their materials. We also know that at least one hacked DNC email released by Wikileaks was altered prior to release. Like with any other information used by journalists, verifying and confirming the veracity of any leaked information is key. If they do report on the content of hacks, journalists might contextualize the information further by noting possible reasons for the hack, such as influencing voters.

One possible approach is to cover the story of the data dump itself, rather than its contents. French journalists took this approach when data from Macron’s campaign was hacked and released just before the election. This informed the public but did not amplify potentially falsified content. This approach may also help to prevent future hacks because it helps to invalidate their purpose.

Fake personae are the second key tool in foreign disinformation campaigns. We now have ample evidence of fake social media accounts and fake freelance journalists publishing articles in online outlets. These fake personae have duped major media organizations as well as users. Twitter estimates that there were over 50,000 Russian-linked social media accounts active on its platform during the 2016 election campaign. Twitter is now notifying users who followed, favorited, retweeted, or replied to these accounts. That ranges from Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) to major media outlets who featured tweets from these fake figures.[8] (Note that this does not necessarily include everyone who saw or engaged with this content.)

Media outlets featured these tweets in multiple ways: they embedded them in articles as examples of how “ordinary people” reacted to news; they quoted them to showcase myriad opinions on the election; they embedded the particularly funny or pithy tweets to increase hits. To take one example, journalists often have to produce a reax story (reaction story) to an event within two hours so they pull some pithy tweets. It’s easy; it generates thousands of clicks; it probably fulfills the journalists’ quota for stories that day. But it’s also dangerous. Social media are key sites for information laundering, where Russian-linked groups post and amplify information, but maintain plausible deniability about Russian involvement.[9] An account might seem to be real, like that of Jenna Abrams who seemed like a Trump-supporting all-American woman. She later turned out to be someone generated by the Internet Research Agency, the St. Petersburgbased Russian troll farm.[10] One study found that 32 out of 33 major American news outlets featured tweets from the Internet Research Agency in their stories as evidence of American partisan opinion.[11] If news articles embed these types of tweets, they may make readers think that there is more widespread support for certain viewpoints than actually exists in reality.

The incentives — speed and clicks —make it hard to change the behavior that led media outlets to feature those tweets.

Reax stories are not going away, but there are simple ways to make them more reliable. Embedding tweets from “ordinary people” is really an updated version of the “vox pop” or “man on the street” quotation that we have seen in articles for decades. Journalists often use “vox pop” to display different or opposing points of view on issues. There were informal guidelines and norms about whom to interview on the street and how. We suggest creating equivalent guidelines to avoid being duped by social media accounts again.

These guidelines need not be complicated. Instead, media organizations can establish simple procedures for verifying which social media posts to feature or freelance journalists to publish. This could be a checklist or it might be one simple step. For example, outlets might commit to only embedding tweets from people whom journalists have contacted on the phone. Verification on Twitter is not enough to ensure a user’s reliability. Nor is a written reply to a direct message. Instead, it is important to contact Twitter users briefly on the phone to check their identity before posting their tweets. It is better to feature fewer tweets because journalists cannot contact a user over the phone than to amplify fake figures.

There are also ways to embed verified social media posts more responsibly. Organizations could simply quote tweets rather than embedding them. If news outlets do embed tweets, they might consider cutting out the portion showing replies/retweets/favorites. The Financial Times has started to do this. It avoids providing a potentially inaccurate snapshot in time; it also avoids over-legitimizing tweets by providing social proof of the number of retweets or favorites; it avoids reflecting misleading numbers because many retweets or favorites may have come from bots.

Still, news organizations often need to report on extreme or suspicious figures, such as neo-Nazis. In those cases, organizations might consider simple techniques to avoid further amplification. Don’t link back to their tweets or posts; use a screenshot or quote them instead. Don’t include their Twitter handle. Ensure “non-follow tags” are enabled on news sites for those links so that any clicks don’t register as hits for them.

The same guidelines might apply to publishing freelance articles. It takes a few moments to speak with an author on the phone to verify their identity. Those few moments can safeguard against destroying years of credibility if an organization avoids publishing fake freelancers.

Recommendations

Journalists and editors can avoid amplifying disinformation. They can also do more than avoidance by taking positive steps to engage their audiences and educate them about Russian attempts to interfere in American democracy.

2. How to Increase Literacy about Foreign Interference

Many discussions about combatting Russian government attempts to undermine U.S. democracy call for greater media literacy. This is meant to build resiliency against manipulated social media or falsified information by teaching citizens how the media function and how to identify fake news. Often, these discussions imply that media organizations should take on the task of media literacy. The evidence suggests, however, that this kind of education needs to be undertaken by governments or civil society, for example by including a media module in high school social studies.[12]

Media organizations, however, should focus on story literacy rather than media literacy. Story literacy focuses on how to help users understand a particular story, rather than how to understand media as a whole. Story literacy means that media organizations take responsibility for helping their consumers understand complex and developing stories, such as Russian attempts to undermine American democracy.

Russian malign influence operations are complicated, murky, and often hard to understand because they take on multiple forms. Story literacy on these issues is not just a matter of civic responsibility for news outlets. It can also generate greater user engagement, because users will turn to an outlet for digestible, comprehensible, and compelling information.

Story literacy can take many forms. It means repeating, summarizing, and reminding. Remember that most readers dip in and out of following stories. As media critic Jay Rosen has put it, journalists need to remember that most people are walking into the movie half-way through and need a plot summary to get them up to speed.[13] It may be less exciting than a scoop, but a 200-word article summarizing the Trump-Russia story may be more useful.[14]

Outlets can also create more frameworks and timelines for complex stories like financial transactions and potential money laundering by figures linked to the Russian government. The Washington Post creates good network diagrams of key figures showing their photographs and links between them. Or organizations might create a dedicated vertical to Russian activities, like NewsDeeply does for stories like Syria. This would create space for more stories around this complicated topic and make it easier for users to find background information and get up to speed swiftly. The Guardian now embeds explanations in the form of Q&A within complicated stories. Vox’s explainer cards are another example of easy-to-read and simple ways to break down complicated topics.

Part of story literacy can also be debunking. Debunking is an uphill battle. It might not even be winnable: the debunkings of the top 50 fake stories on Facebook in 2017 generated about 0.5 percent of the engagement of the fake stories themselves.[15] But fact checks do still change minds. Leticia Bode and Emily Vraga’s study on changing misperceptions about Zika found that fact checking resulted in a 10 percent decrease in overall misperceptions.[16] Outlets could consider creating regular debunking stories and easily shareable meme debunking. If the fact checks and debunkings change a few people’s minds, they are still worth it.

Finally, story literacy also means greater transparency. Nearly a decade ago, David Weinberger suggested that journalists take transparency as their highest value rather than objectivity.[17] This suggestion rings even truer today. Transparency can increase trust in reporting; it can also guard against manipulation. Transparency is not simply a service; it can drive readership, viewership, and listenership too.

We suggest doubling down on two types of transparency: in reporting practice and in reporting procedure.

There are many swift and simple ways to bolster transparency in reporting practice. One is to participate in the Trust Project, a new initiative that pushes for standardized disclosures in news articles, such as information on the journalist’s expertise and the sources used.[18] Consider moving to these standards like better story labelling sooner rather than later. It is also possible to introduce better disclosure practices for freelancers. The Conversation is a site where academics publish their research in op-ed format. The academics are required to disclose their sources of funding and any possible conflicts of interests. Other news organizations might adopt those disclosures for freelancers to guard against fake freelancers or other manipulation.

Individual journalists can also include more within stories on how they decide whether sources are trustworthy or how they found a source (within the boundaries of what journalists can reveal). Some mention of sources has of course long been standard practice. But journalists might remember that readers do not necessarily understand phrases like “off the record” or “a source close to X.”[19]

Journalists can match more transparency within stories with more transparency in overall procedure. Transparency in procedure means explaining to readers more about how journalists do what they do. This is particularly important for stories on Russia where many of the sources will only speak on deep background or off-the-record. Readers might love a story about how journalists decide whether to trust a source or a story about an article that journalists could not write because they could not verify source material.

If detective novels and crime procedurals are so popular, why not journalism procedurals?

Most readers do not know any journalists and have never been in a newsroom. Journalism is a black box to them. One solution is for journalists to open up the black box and write procedural articles that explain how they found sources or stories. This might sound boring, but procedural stories can be deeply compelling and are often surprisingly popular. Serial and S-Town were runaway podcast hits, partly because the reporters embedded themselves, their reactions, and their search for further information into the narrative. If detective novels and crime procedurals are so popular, why not journalism procedurals?

Changing journalistic practice and providing greater transparency to create greater trust have been regular features of journalism throughout its history. By-lines emerged in the interwar period to assure readers about the individual sources of their news. We find ourselves in another period where trust in journalism has declined. New procedures can revitalize trust. They also remind us that we need to start planning for future problems today.

3. How to Anticipate Future Problems Today

It is hard to plan for an unknown set of future problems with faked materials when we are still struggling to deal with our current crop of fake social media accounts, bots, and foreign interference. But faked audio and faked video are coming. Verification will not be impossible, but it will not be simple, either. The right procedures will be key.

Organizations should create a regular schedule for revisiting and updating social media and verification guidelines. This is a rather simple change to promote organizational vigilance. In a swiftly changing social media environment, even guidelines created before the 2016 election can now seem outdated. Setting a regular time to update guidelines creates an in-built mechanism to keep organizations up-to-date on the latest developments in social media and pushes editors to think about how their newsrooms might adapt.

Another method to remain vigilant about disinformation and faked materials is to create a beat reporter on the subject, akin to Craig Silverman’s role at BuzzFeed. This ensures that news organizations know and report on the newest developments in falsification.

Within the broader organization, news outlets might assign responsibility for thinking about this issue to a C-level executive within the news organization. That person would take charge of finding appropriate verification solutions to emerging threats. By thinking now about future problems of faked and weaponized information, organizations can tailor solutions to their own organizational structures. They can develop procedures to prevent problems, rather than have to issue corrections that undermine their credibility after the fact.

All organizations struggle with accurate planning for a future they cannot predict; the nimblest ones both plan for the future and establish procedures to revisit continually their assessments of future developments. In the case of news organizations, we can be fairly certain that faked materials, faked social media accounts, and weaponized information will continue, even if we cannot be certain of the forms they will take.

We sometimes take for granted the openness and freedom of our media. They are a source of strength; they are also a source of vulnerability when bad actors seek to exploit that freedom by turning Americans against each other. There are no easy answers on how to balance between combatting the nefarious effects of foreign interference and protecting the very freedoms that interference seeks to undermine.

No matter how we proceed, the vibrancy and revitalization of free media remain essential for a resilient democracy. For all the proclamations that social media have made major news outlets obsolete, these more traditional organizations still drive the conversation in more circles than we might think. Trust in “the media” may be low, but trust in “my media” — the specific news outlets that a citizen uses — is still relatively high.[20] Many commentators are focusing on how to regain trust. But journalists and editors also need to think about how to retain trust from new and loyal users. Sometimes that means new procedures to avoid succumbing to disinformation; sometimes that means updating journalistic procedures like verification for the social media age; sometimes that means remembering that the media still very often sets the agenda and needs to take that responsibility even more seriously than ever.