Reactivating Vacant Buildings: Three Approaches from Germany

In May of this year, GMF’s Urban and Regional Policy Program (URP) awarded Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse (Berlin) and Jacqueline Taylor (Detroit) a grant to support follow up actions from ideas curated at BUILD: URP Urban Innovation and Leadership Dialogues. Inspired by the BUILD 2017 breakout session “Conners Creek Power Plant: Tactical Preservation for Detroit’s Industrial Legacy,” their project aimed to pilot a transatlantic exchange of best practices in the reactivation of vacant buildings.

The project addresses challenges shared by cities in the United States and Europe that are experiencing demographic and/or structural change. The intention was to explore initiatives that seek solutions to long-term vacancy through a range of stakeholder constellations and in a variety of buildings and use types. Their first field trip was to Germany, where they visited Bremen, Chemnitz, and Halle (Saale).

Wurst Case Scenario: The Temporary Use Agency in Bremen

In Bremen, a visit to the ZwischenZeitZentrale (Temporary Use Agency) revealed a multitude of possibilities. The visit began in the agency’s own offices, which are located in the apt but comically named Wurst Case, a repurposed administrative building in a former Hemelingen District sausage (Wurst) factory.

The city of Bremen has undergone dramatic social, environmental, and structural changes due to the decades-long demise of the port industry. Lack of public funds and low market momentum have meant that traditional strategies for the reuse of vacant commercial and industrial properties have failed to gain traction. However, while original uses have continuously diminished, demand for low-cost cultural and creative spaces has increased. Seeing potential synergies, Bremen formalized new tactics for reactivating vacant buildings through the ZZZ, founded as an umbrella agency for residents seeking space for creative ventures and start-ups.

The ZZZ is the product of Bremen’s 2007-2009 reconception of the harbor area, in which they experimented with temporary use and intermediate activation of vacant buildings and land. An intermediate use agency piloted as part of this project was so successful that the city decided to expand the strategy.

The ZZZ represents a new, highly successful, low threshold approach to addressing vacancy and reuse needs through both a single point of contact and a simplification of bureaucratic processes. Users communicate solely with the ZZZ, receiving help with permits, liability insurance, and occasional discretionary funds for new intermediate uses. The strategy has proven effective in supplementing district restructuring and revitalization processes, as well as supporting local real estate goals.

Another ZZZ project, Bay Watch, transformed vacant land in the former harbor area into “a space for experimental architecture, permaculture and art in public space.” Temporary wood frame structures and converted camping trailers provide residential space; nearby, a library, a stage, and a greenhouse are constructed from repurposed building materials. The site is ringed on three sides by factories, warehouses, and other active industrial uses, reminiscent of the once vibrant habor. Here, the ZZZ mediated transactions across public land owner and private occupant agreements. In Blumenthal, a small town on the edge of Bremen where empty storefronts line the pedestrian zone, the ZZZ facilitated a project staging arts interventions on public land and providing owners of a café and gallery with shared space. Nearby, a massive red brick factory complex, the former Spinnery, awaits new plans for reactivation.

The library at Bay Watch. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

The stage at Bay Watch. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Empty storefronts line the pedestrian zone in Blumenthal. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

The spinnery in Blumenthal awaits new strategies. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Temporary use projects in Bremen present a way to flexibly react to a range of urban and site development challenges while generating interest in vacant spaces that might otherwise fail to attract more traditional investors. The projects facilitated by the ZZZ kept vacant buildings from falling into disrepair and encouraged pedestrian traffic and eyes on the street, thus helping to prevent vandalism. Strategic integration of temporary uses into urban development and economic promotion additionally tested new forms of coordinated cooperation between private users and the city and between city departments. The work of the ZZZ effectively reduced municipal costs as temporary uses of municipally-owned properties shifted operating and maintenance costs to temporary users; the ZZZ agency also bore responsibility for managing the coordination of temporary uses. The ZZZ’s work supports and strengthens the local cultural and creative economy by providing appropriate spaces at low-cost, thus realising a new perspective for Bremen’s future development.

The Sun Rises on Sonnenberg: Reactivation Strategies in Chemnitz

The study’s second stop was in Chemnitz, a medium-sized city in the state of Saxony. Like many cities in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), Chemnitz experienced a sharp decline in population after the opening of the inner-German border. The city, which boasted 302,000 residents in 1989, hit a population low of 240,000 residents in 2011, a 20 percent reduction. In recent years, the city has seen modest growth, but not the recovery experienced by other cities in the state such as Leipzig or Dresden.

The drastic population decline over this 20-year period has left a large percentage of vacant housing units, in particular those in unrenovated industrial-era buildings. Moreover, complex title issues have exacerbated reactivation as the city administration lacks the resources to research and locate absentee owners. Some individuals may even be unaware that they are property owners, a peculiarity of property restitution stipulations resulting from German reunification.

One of the hardest hit neighborhoods in the city is Sonnenberg. Here, whole blocks of multi-family housing still stand empty, their boarded up windows decorated with pictures made by local schoolchildren.

Blocks of houses stand empty in Chemnitz’ Sonnenberg district. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Blocks of houses stand empty in Chemnitz’ Sonnenberg district. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Blocks of houses stand empty in Chemnitz’ Sonnenberg district. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

The decline in population in Sonnenberg also resulted in the redundancy of a range of civic buildings, some of which are historical monuments. The reactivation of these buildings presents a particular problem, as renovation in accordance with historical preservation law is costly and often discourages investors when other properties are available.

To address these problems, the City of Chemnitz created the Agentur StadtWohnen (Agency for City Living) in 2006, whose job it is to facilitate cooperation between building owners, the city, and potential users and investors. The agency is responsible for finding the owners if they are not known, and arranging a change of ownership if desired. According to project manager Martin Neubert, 140 buildings have been identified and monitored to date. Change of ownership has been successfully arranged for 50 of these, and 40 properties currently remain available for activation by new users and/or investors.

At the time of the visit in September 2018, a private developer had purchased several multi-unit buildings and was converting these into affordable housing for artists and other creatives — rough-finished apartments will be rented for just 1€ per square meter plus utilities. As an outward sign of interior changes, the developer opted to paint building window trims with bright and unusual colors.

Bright trim helps to make the changes in this residential building more visible. Photo: Jacky Taylor.

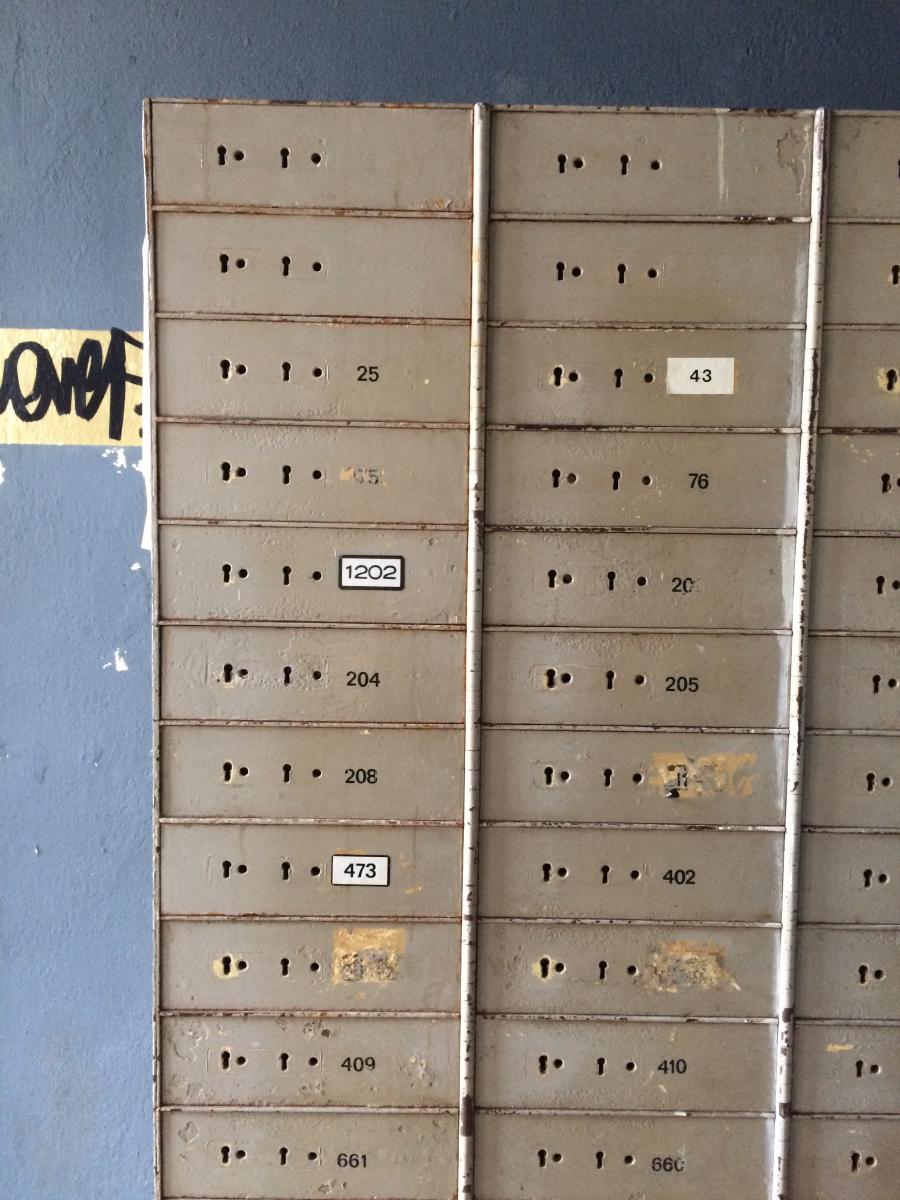

A block away, a vacant 1920s bank building has been converted into a center for creative industries, complete with a café where tellers once stood and tangible elements connecting to the past such as remaining safe deposit boxes and an old coat check stand.

A bank building from the 1920s has been converted into a center for creative industries. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

A bank building from the 1920s has been converted into a center for creative industries. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Traces of the past: safe deposit boxes still stand in a bank building from the 1920s which has been converted into a center for creative industries. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Similar to the City of Bremen, Chemnitz is focusing on highly-mobile younger residents, the cultural and creative industries, and DIY-ers as potential users of vacant spaces. However, while Bremen has focused on temporary reactivation as a prelude to permanent reuse, Chemnitz has set the focus on activating absentee owners and moving buildings from vacancy to permanent reuse through the work of the Agentur StadtWohnen.

Artistic Freedom in Halle’s Freiimfelde District

The third and final stop in this trip was to the town of Halle (Saale), where the district of Freiimfelde has become a playground for street artists and a hotbed for new forms of participatory democracy.

Freiimfelde, a vibrant mixed-use area from the early 20th century with red brick industrial buildings, small courtyard workshops, and typical industrial-era housing, fell prey to the same demographic shifts as Chemnitz’ Sonnenberg. The population of Halle as a whole dropped from 310,000 residents in 1990 to just 239,000 today, a change of -23 percent. Divided from the rest of the city by a highway and train tracks, Freiimfelde was particularly hard hit. In 2011, the vacancy rate among the industrial-era housing here was a whopping 40 percent. Vestiges of this past are still visible in some streets, but recently the more eye-catching scene is that of the brightly-colored massive murals.

Unrenovated and vacant industrial-era housing. Just 10 years ago, almost all of Halle’s Freiimfelde district looked like this. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

Murals enliven the ground floor of this unrenovated house. Photo: Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse

A mural and an oversized beach chair brighten up a vacant corner lot in Halle’s Freiimfelde district. Photo: Jacky Taylor

The murals are the work of the Freiraumgalerie (translated as Open Space Gallery), a citizen-based group with a strong democratic ethos whose members asked: “who owns the city and who has the right to influence its form and appearance?” Staging an “All You Can Paint” festival in 2012, they brought color, vibrancy, and attention back to Freiimfelde for the first time in more than a decade and launched a process of citizen-led urban development that continues today.

The macroscopic approach of the “All You Can Paint” festival envisioned not only the transformation of gray, dilapidated facades, but the co-creation of a new vision for Freiimfelde that would bring together young creatives, local residents, and the city.

The group’s involvement gained momentum over the coming years, expanding to incorporate residents, in particular local children. These activities attracted the attention of a range of actors. In 2015, the Montag Stiftung Urbane Räume (Montag Foundation for Urban Spaces) opened the Urban Neighborhood Freiimfelde, a neighborhood center in the main street, in cooperation with the Freiraumgalerie and the City of Halle. The neighborhood center is unique in Freiimfelde, where gathering spaces for residents are othewise rare. The cooperation between these three actors has led to a range of site-specific activities, including a citizens’ urban plan, the purchase of a 6,000 square meter abandoned lot to be codesigned with residents into a new park, and the development of a construction playground, a first for Halle.

Over the last six years, the vacancy rate in the industrial-era housing has dropped to 16 percent as investors are drawn to the developments in Freiimfelde and local citizens with penchants for DIY have purchased the inexpensive properties still for sale. In addition, the Urban Neighborhood Freiimfelde and the City of Halle contribute to an annual neighborhood fund to which anyone with an idea or project for Freiimfelde can apply. The commission approving or rejecting these applications comprises a range of local actors, including from the citizens’ group, the church, and the school.

Lessons Learned

In each of the cases studied, the cities found a way to facilitate already present actors and capitalize on existing local capacities.

The City of Bremen has leveraged a growing creative sector to address a wealth of vacant properties, a step which nevertheless required a rethinking of typical bureaucratic processes and the needs of young creative actors. Chemnitz took a slightly different approach based on their more pressing issue of absentee owners, focusing more on activating owners than users. Halle buoyed local, grassroots movements through small investments and municipal support, embedding their ideas and practices in official planning structures.

The three cities all relied on high visibility in their projects in order to create curiosity and interest in these new developments. Strategies included branding, public events, websites, and social media campaigns.

Thirdly, all three cities relied on the private sector to implement these strategies. Both Bremen and Chemnitz contracted their agencies to existing planning offices, in Halle the Freiraumgalerie has since developed into a planning collective. Public-private cooperations play an important role, in particular when the private implementing agency is locally-based, with a wealth of local knowledge and passion for the subject and area.

Finally, although each of the three cities continues to have a large number of vacant properties and land, the activities described here represent a way of changing public perception from one of stagnation and decay to one of dynamic change and redefinition. Even the partial reactivation of large buildings, such as the Wurst Case, created a momentum which could be carried over to other properties.

To conclude, the three cities showed that incremental, high visibility reactivation that engaged young, creative, and DIY-oriented users could effectively change the public perception of neighborhoods and create both economic and social benefits. Such strategies prove to be powerful tools that leverage existing capacities in new ways and supplement traditional programs for the promotion of urban redevelopment.

Next Stop: Rust Belt

The next field visit in this study will be to the U.S. Rust Belt, where Dellenbaugh-Losse and Taylor will explore cases in Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh this November.

Jacqueline Taylor (PhD - Lead Historian/Cultural Landscape Specialist at the city of Detroit and Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse (Urban researcher and independent policy advisor)