Reactivating Vacant Buildings: Approaches in the United States

In May of this year, GMF’s Urban and Regional Policy Program (URP) awarded Mary Dellenbaugh-Losse (Berlin) and Jacqueline Taylor (Detroit) a grant to support follow up actions from ideas curated at BUILD: URP Urban Innovation and Leadership Dialogues. Inspired by the BUILD 2017 breakout session “Conners Creek Power Plant: Tactical Preservation for Detroit’s Industrial Legacy” their project aimed to pilot a transatlantic exchange of best practices in the reactivation of vacant buildings.

The project addresses challenges shared by cities in the United States and Europe that are experiencing demographic and/or structural change. One of the goals of the project was to explore initiatives that seek solutions to long-term vacancy through a range of stakeholder constellations and in a variety of buildings and use types.

On their first trip, Mary and Jacky visited three cities in Germany and learned about grassroots efforts to activate vacant housing through street art, innovative techniques for activating absentee owners and public-private partnerships for intermediate use. On their second trip, they sought to learn from initiatives in Cleveland and Detroit. Similar to the case studies visited in Germany these two cities have also suffered demographic and structural change brought on by long-term deindustrialization and are home to a high number of large-scale vacant buildings.

Grassroots and Investor-Led Reactivation in Cleveland

The first stop was Cleveland’s St Clair Superior neighborhood, which is home to a number of industrial buildings currently in various states of vacancy/occupancy. One innovative approach to repurposing a complex of industrial buildings that share parking space and accessibility off the main road is the Hamilton Collaborative. Like many of the projects we explored in Germany, this project was run by a group of individuals interested in pursuing their own initiatives in a shared space – a large complex of former industrial buildings offered a wide variety of different spatial typologies for an even wider range of users. The co-located enterprises of the Hamilton Collaborative were able to tailor these spaces to their needs; interiors ranged from basic to highly polished, demonstrating the possibilities for activating space without having to rehabilitate the entire building or complex of buildings. Enterprises in the Hamilton Collaborative included an architectural salvage retailer, a full-service architectural firm, a compost start-up focusing on the circular economy in gastronomy, a local street festival, a woodworking fablab, and a community motorcycle garage offering tools, training and services to motorcycle owners.

The Hamilton Collaborative is home to a community motorcycle garage...

And storage area for parade floats.

The buildings are rented by a primary lessee, the architectural salvage retailer, who then sublets to other businesses. While management of the buildings is conducted cooperatively, each tenant is separately responsible for their own interior design and retrofitting as needed. One disadvantage to this as Jessica Davis co-owner of Rebuilders Exchange admitted, it’s a full-time job managing the building and various spaces, making sure everything is maintained, in addition to running her own business. Which reminds us that having a separate entity manage the buildings and rental agreements such as the ZwischenZeitZentrale (Temporary Use Agency) we found in Basel, makes sense, when possible.

The availability of inexpensive, raw space has provided a form of bottom-up incubator for a variety of enterprises. In addition, the co-location of businesses has a number of proven advantages to both business owners and consumers, including shared resources, common networks, development of a broader community interested in similar services, and products and services that aim towards social progress and equitable distribution of economic development opportunities.

Not far away, the Tyler Village demonstrated an investor-led alternative to incremental reactivation. Tyler Village is a former industrial complex home to the former Tyler elevator factory and totals a whopping 1 million square feet of interior space. Similar to the Hamilton Collaborative buildings, Tyler Village contains a wide range of spatial typologies, from manufacturing and storage sheds to former administration buildings.

Tyler Village stretches over a whopping 1 million square feet.

The former administrative space now hosts a café.

It was not possible for the developer to acquire a line of credit that was sufficient to renovate the entire space at once; instead, he developed an innovative financial model to incrementally rehabilitate the space. Leasing portions of the space with the promise to turn it over after de-risking it, i.e. removing hazards, repairing or installing an HVAC system, checking and/or improving the wiring, the developer returned to the bank to request a mortgage extension based on the secured rental income, which he then used to de-risk and otherwise prepare the space for the future tenants. The former administrative building, which still boasts representative furnishings and decorations, is home to a café, tech startups, and, until recently, a working furniture showroom. This building demonstrated a superior level of interior finishing, with smooth white plaster walls, carpeting, and new elevators.

Until recently, a furniture store had a working showroom on the top floor of the former administrative building.

Tech start-ups inhabit the highly-finished middle floors of the former administrative building.

The adjacent former manufacturing complexes were much rawer and housed salvaged furniture workshops, storage for the local flea market, and, until recently, also a violin manufacturer. This building also housed a charter school, which added to the impression of a bustling new quarter.

The neighboring former manufacturing space is still raw.

Looking out towards downtown Cleveland, where adaptive reuse projects are also underway.

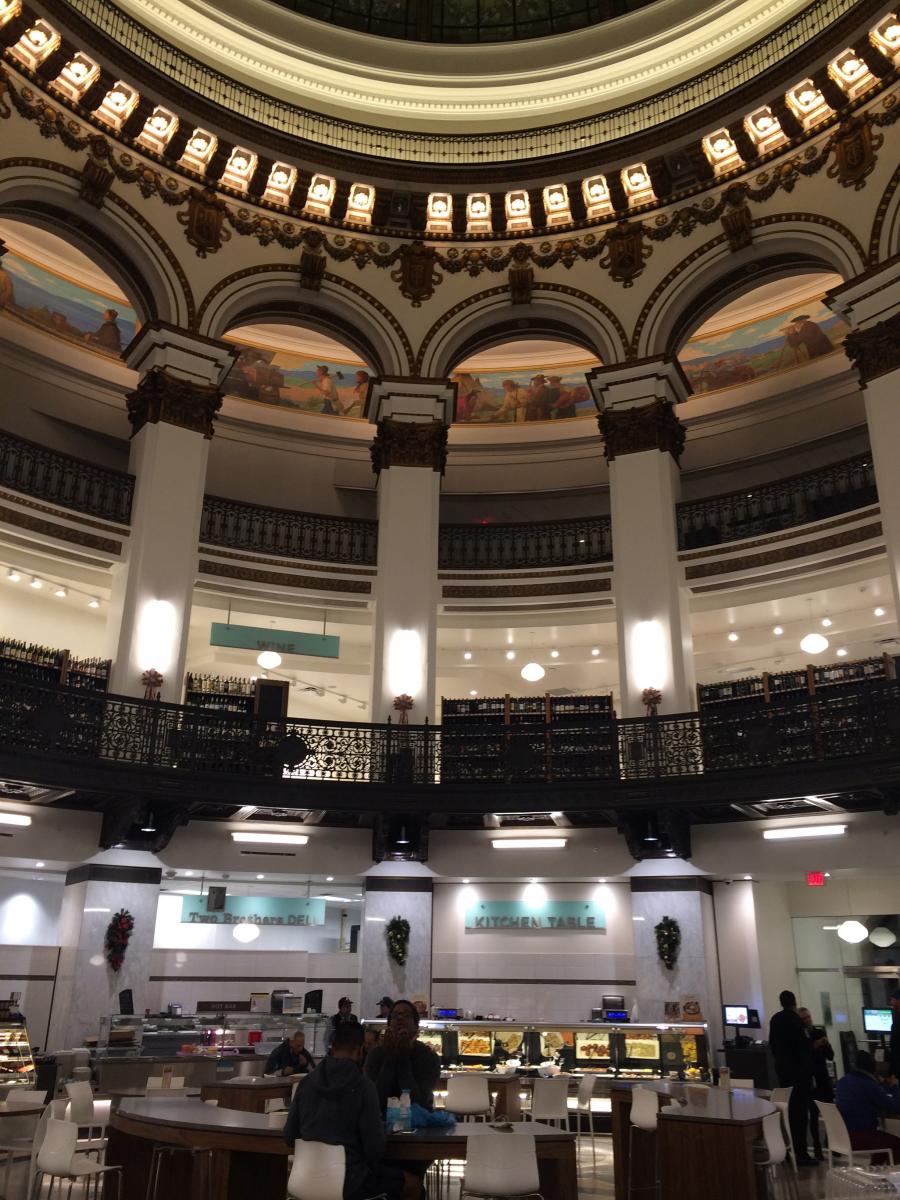

These spaces follow a general trend of adaptive reuse in Cleveland, which was apparent in the city center as well, where the removal of 1970s brown glass facades have revealed intricate stonework beneath, and a former bank building has been repurposed as a grocery store.

A former bank building in downtown Cleveland has been repurposed as a grocery store.

Detroit: Innovation through Tactical Preservation

Heading back to Detroit, Jacky and Mary dove into the concept of tactical preservation, a technique which is being piloted by the City of Detroit. GMF organized at BUILD, in partnership with the City of Detroit and DTE Energy, a Lab entitled: “Tactical Preservation for Detroit’s Industrial Legacy, in the beautiful turbine room of Conners Creek Power Plant, a defunct space with little support for adaptive reuse on the part of property owner Detroit Energy Company (DTE). The idea was to generate adaptive reuse concepts for one particular space that could spur development across the entire power plant complex. Discussions around the viability of such possibilities are ongoing.

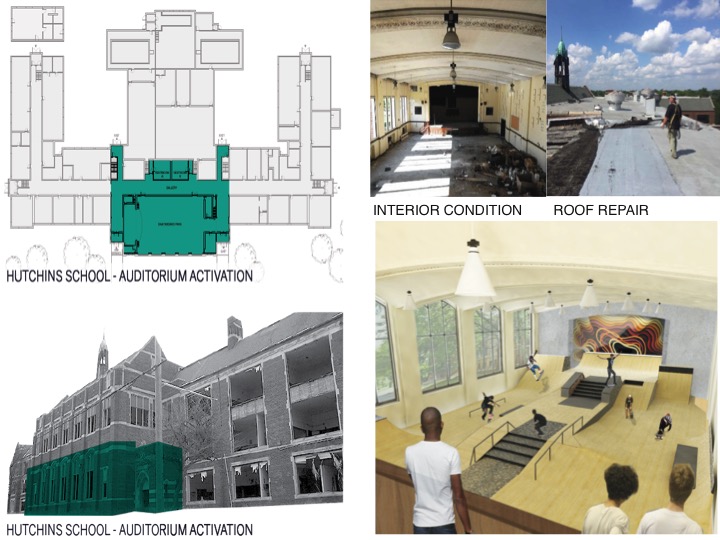

Two other properties are also in the process of being adapted to new uses through a partial, phased approach. The Hutchins School is owned by an independent architect/developer and part of a neighborhood complex that includes the massive Hermann Kiefer Hospital. The school recently received a temporary use permit for development of the auditorium into an indoor skate park, as a resource for local youth. What remains of the building will be secured for future use as the neighborhood is repopulated.

Image: Hutchins School, Ron Castellano (Developer/Architect) with the City of Detroit Planning and Development Department.

Another project, the Alger Theater is a long-term labor of love undertaken by the Friends of the Alger, who over the course of 13 years have been gradually transforming the space, creating a roof-top bar then, with the promise of tenants in hand, adapting the outer edges of the building into storefronts. Funds were crowd-sourced through the Friends organization as well as through a City-run award program, Motor City Match intended to encourage adaptive reuse of vacant spaces with new businesses. The final project will be to restore the central theater space to its original glory, complete with lavish authentic furnishings.

Bringing it all Together

The projects visited in these two cities highlight the central role of private investors in the reactivation of buildings and landscapes in the American context and the relative rigidity of institutional structures. While the Hamilton Collaborative is a community-based grassroots initiative, it still functions within the usual landlord-tenant constraints. As discussed with our interview partners, the rigidity of building codes acted as salient barriers to the intermediate and alternate uses that we saw in Germany. In addition, the cases visited in Cleveland and Detroit demonstrated the central role of tax write-offs as a vital instrument for incentivizing the reactivation of vacant buildings. Furthermore, both practical constraints such as adjacent market potential, as well as an emotional attachment to buildings in the United States influenced their viability for adaptive reuse, even by means of a phased approach. Identifying buildings with support for a phased partial adaptive reuse, as well as the appropriate funding stream to support them appears imperative in the context of the United States. The range of differences in approach to adaptive reuse between the United States and Germany indicates a high potential for continuing knowledge transfer and learning opportunities on this topic.