Pivotal Powers 2024: Innovative Engagement Strategies for Global Governance, Security, and Artificial Intelligence

States outside the transatlantic alliance have gained leverage in international affairs in recent years and, with that, the potential to significantly reshape the global order. Engagement with these "pivotal powers", which include Brazil, Indonesia, India, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Türkiye, is of paramount importance for Europe and the United States.

"Pivotal Powers 2024: Innovative Engagement Strategies for Global Governance, Security, and Artificial Intelligence" offers tactics for enhancing Western cooperation on global challenges with these countries. This report builds on GMF reports from 2012 and 2023.

Download the full report by selecting "Download PDF", read the foreword, introduction, and policy recommendations below, and explore the individual topic chapters:

- Multilateral Reform and Minilateral Cooperation

- Pivotal Powers and International Security: Toward Flexibility

- The Dawn of Pivotal Powers in Artificial Intelligence

Foreword

By Alexandra de Hoop Scheffer

Recent years have witnessed a significant shift in the global order toward multipolarity. UN General Assembly votes on Ukraine and Gaza, in particular, served as a wake-up call for the United States and its European allies. These votes demonstrated that transatlantic priorities and policies no longer reflect a worldwide consensus and that the era of a global majority’s acceptance of Western approaches to international challenges has ended. The limited US and European anticipation of such divergence, however, underscores the importance for the transatlantic partners of expanding their understanding of the positions of countries beyond the confines of their alliance.

***

In the context of an increasingly contested post-World War II global order and its US leadership, new central players have emerged in key areas of international politics. This shift is particularly evident in mediation efforts involving countries such as Brazil and Qatar, which have undertaken their own initiatives in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. In addition, India’s engagement in minilateral formats is shaping cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, and Türkiye’s bid to join the BRICS demonstrates that NATO membership does not preclude alternative alignments.

The increasingly important geopolitical role of these middle powers is undeniable. Unlike the United States and China, but like many European countries, these powers are not “great powers” in terms of military expenditure or economic performance. However, they possess critical assets that they increasingly leverage to influence global affairs. These “pivotal powers” are likely be at the forefront of shaping the future world order.

This publication, “Pivotal Powers: Innovative Engagement Strategies For Global Governance, Security, and Artificial Intelligence”, serves as a crucial foundation for more effective cooperation with these powers in the evolving global landscape. This report builds on GMF’s earlier work on “global swing states”, a concept coined by GMF in a 2012 publication and revisited in the 2023 study “Alliances in a Shifting Global Order”. Written by experts on GMF’s geostrategy and innovation teams based in the organization’s offices on both sides of the Atlantic, this report is a prime example of pooling topical and geographic expertise. The collaborative and cross-cutting approaches presented here, combined with in-depth qualitative research over several months, allow GMF to spearhead the intellectual and policy debate on innovating transatlantic relations in a changing geopolitical environment.

The research concentrates on three critical arenas of international relations: multilateral organizations, security, and artificial intelligence. It presents the perspectives and priorities of pivotal powers—namely Brazil, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Türkiye—regarding these challenges, and their assessments of US andEuropean approaches to address them.

***

The focus of this publication is about listening to and learning from pivotal powers. The United States and Europe must extend the scope of their relationships to others if they are to address the growing number of international challenges. They must engage pivotal powers as equal partners in tackling global issues and adapt policies to take into account pivotal powers’ insights.

By fostering more effective engagement with diverse global perspectives, this report aims to prompt a reassessment of US and European approaches to international leadership. This recalibration is crucial for maintaining influence and relevance in the evolving multipolar world order.

Introduction

By Rachel Tausendfreund and Martin Quencez

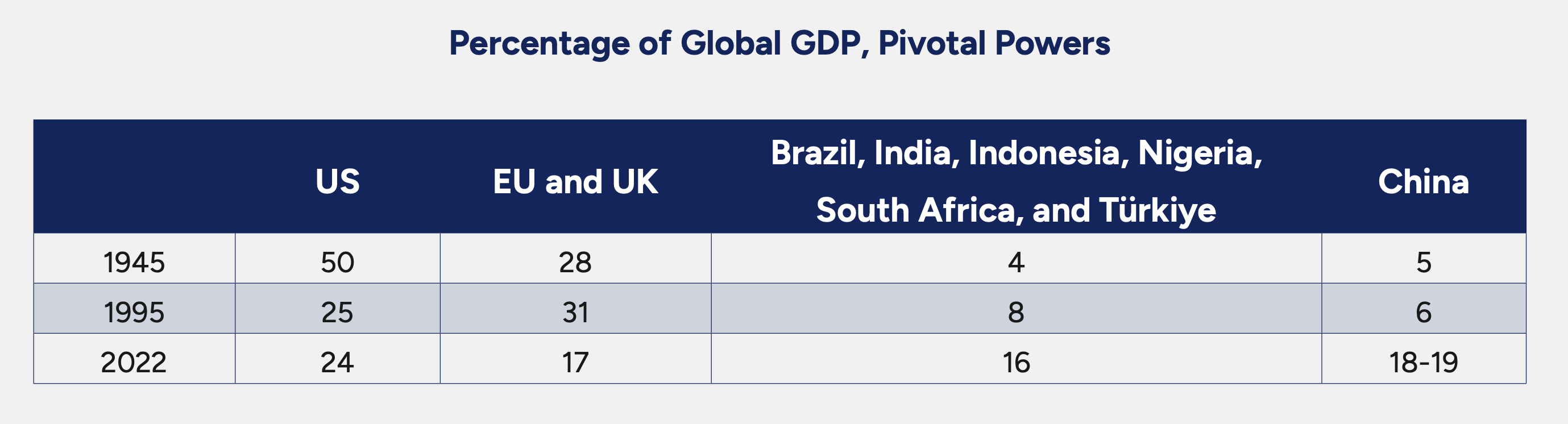

It is time to embrace revision. This is no longer the world of 1945, nor of 1995, when the World Trade Organization was founded (see graphic below). It should, therefore, be obvious that the rules devised then are (over)due for review. Revisionism, however, has two versions, one of which involves a falsified retelling of history. But the other challenges the multilateral status quo, and it is that which should be pursued. This may discomfit the permanent members of the UN Security Council, but the international system must adapt to new circumstances or collapse. In fact, with multipolarity a reality, fragmentation or adaptation is already well underway.

Europe and the United States, rather than resisting the change, must join with partners to constructively revise global systems and practices. The US approach to China’s rise often seems based on a bipolar vision while Europeans and many other middle powers are more willing to embrace a multipolar future. As Dino Patti Djalal, former Indonesian vice foreign minister, argued at this year’s World Economic Forum annual meeting, “21st century global order will be shaped not by major powers, but by proliferation of middle powers.”

This report is the third iteration of a project focusing on these middle powers. The project was launched in 2012 with the publication of “Global Swing States”, in which authors Daniel M. Kliman and Richard Fontaine argued that:

“To defend and strengthen the international order that has served so many for so long, American leaders should pursue closer partnerships with four key nations – Brazil, India, Indonesia and Turkey. Together, these ‘global swing states’ hold the potential to renew the international order on which they, the United States, and most other countries depend."

In the 2023 update, “Alliances in a Shifting Global Order”, we added two countries, Saudi Arabia and South Africa, to the group of “states [that] promise the greatest return on investment”. Now, we offer a further iteration, focusing on those countries among this generally influential group of middle powers of the “Global South” that we deem “pivotal” in specific policy areas.

A central conclusion of the 2023 report was that while all six influential middle powers examined are happy to cooperate with Europe and the United States on many issues, binary (“us-versus-them”) approaches to the great powers are roundly rejected in favor of compartmentalization and hedging. This followed a year of equivocal responses among “Global South” countries to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a development that shocked many in the EU and the United States. But this shock revealed a blinkered vision. South Africa’s and India’s abstentions from the March 2022 UN General Assembly resolution deploring the invasion and calling for a withdrawal of Russian forces reflected a history of choosing nonalignment in conflicts involving great powers. Additionally, many middle powers had (and still have) economic and strategic ties to Moscow—Brazil, for example, relies on Russian fertilizer supplies—and naturally prioritized their domestic challenges over international conflicts. Germany did no less when it insisted on moving forward with the Nord Stream II pipeline despite Russia’s 2014 invasion and annexation of the Crimean peninsula and despite the objections of EU partners and the United States. US President Joe Biden did no less when he met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman in July 2022 to ask for assistance with lowering global oil prices, despite the president’s labeling Saudia Arabia a “pariah” state after the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

The disconnect perceived in many Western capitals did not actually stem from differences in perspectives on Russia’s war in Ukraine. The invasion was widely condemned, if often in thinly veiled terms of maintaining “territorial integrity”. The gap between the West and the “Global South” resulted instead from Europe’s overestimating the centrality of “its” war for the rest of the world and, in Washington’s case, from overestimating the United States’ ability to persuade middle powers to align with coercive measures to isolate Russia.

Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the resulting war in Gaza have magnified the gap. The West and the “Global South” view the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through fundamentally different lenses. For most in the “Global South” and much of the Asian “Global North”, the decades-long conflict is a result of colonialism, national liberation, and anti-imperialism. This has led to stronger support for the Palestinian cause and criticism of Israel. In contrast, Western capitals supported the creation of Israel and see the country in the context of centuries of persecution endured by Jews that culminated in the Holocaust, and in the context of the fight against Islamist terrorism. Europe and the United States emphasize the need for Israel’s security, counterterrorism, and regional Middle East stability, which manifests itself in support for Israeli military actions, albeit with some calls for restraint and varying degrees of domestic controversy.

This fundamental divergence of views shapes reactions to the war in Gaza (public schisms within many Western countries notwithstanding). In a speech before the UN General Assembly, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan expressed powerful criticism of international support for Israel: “Along with children in Gaza, the United Nations system is also dying, the truth is dying, the values that the West claims to defend are dying, the hopes of humanity to live in a fairer world are dying one by one.”

The wars in Ukraine and Gaza have undeniably reflected Security Council dysfunction, as Russia has vetoed all draft resolutions regarding its invasion of Ukraine. In addition, four ceasefire draft resolutions for Gaza have been vetoed, three by the United States and one by China and Russia. Many see a broken system, but no will or consensus to reform it has materialized. An optimistic person may say that both, however, are building, as evidenced by the adoption of the Pact for the Future, a declaration to reimagine the multilateral system. It includes language calling for a more “representative, inclusive, transparent, efficient, effective, democratic and accountable” Security Council. The United States, the United Kingdom, and France have underscored their commitment to this, and the Biden administration has supported important progress toward reforms including text-based negotiations. This momentum may have, however, been short-lived. The incoming Trump administration is unlikely to invest significant effort in multilateral reform.

Multilateral reform is high on the agenda of all pivotal powers, but other global governance and cooperation alternatives have already arisen in the form of a web of important minilateral groupings, from the BRICS and the G20 to the Quad and Just Energy Transition Partnership. Whatever the form of cooperation, Europe and the United States should focus on making progress with these institutions, and with middle powers directly, on issues on which collaboration is desired, despite disagreements in other areas.

What issues and what topics offer the best results from, or return on, an engagement effort? This is the question we attempt to answer by focusing on middle powers that are particularly important or influential—or pivotal—in the policy areas of global governance, security, and technology.

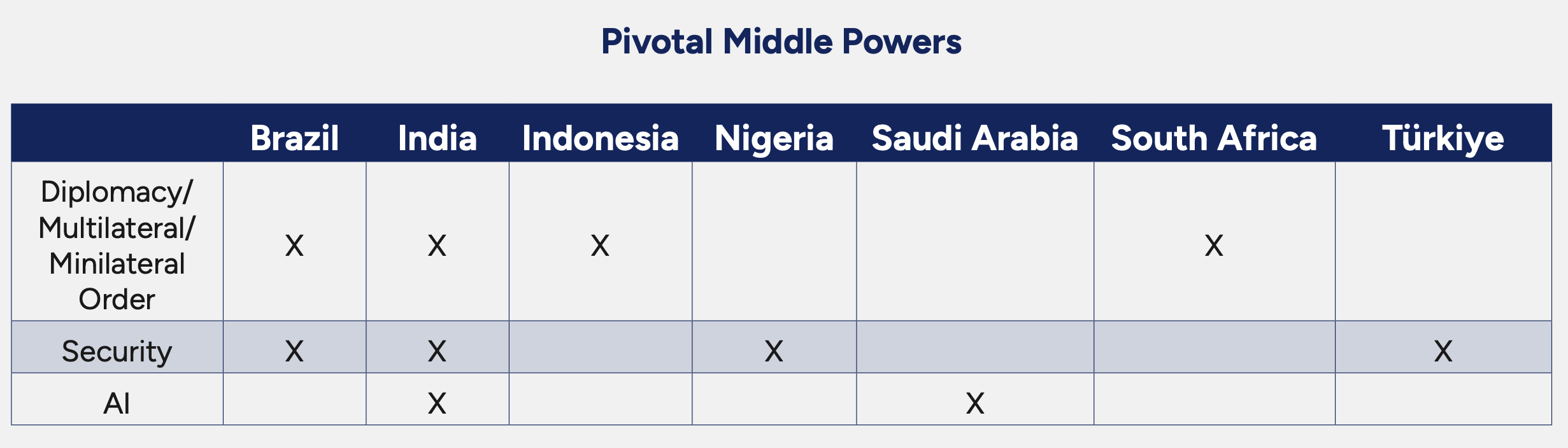

To manage an otherwise unwieldy undertaking, we focus in the following chapters on two to four pivotal powers of the “Global South” for each policy area (see graphic below), acknowledging that in these areas other middle powers may also be pivotal. On the topic of global governance, or multilateral and minilateral cooperation, we examine Brazil, India, Indonesia, and South Africa as highly engaged, diplomatic heavyweights. For international security, we concentrate on the priorities and preferences of Brazil, India, Nigeria, and Türkiye. As regional leaders, these four states are pivotal players in addressing nearby security challenges that have global consequences. And for technology, we highlight India and Saudi Arabia, examining their comparative advantages on the artificial intelligence (AI) value chain, and the opportunities and risks arising from this.

We have adapted our methodology for this study by adopting a journalistic process that uses interviews with researchers and policymakers from the selected countries, and research from local experts, to get an inside view of government priorities. The report aims to provide a detailed understanding of these countries’ perceptions of challenges related to the multilateral system, global security, and AI, and to explain the narratives that they promote in these areas. Gaining a better comprehension of their arguments—as disputable as they may be from an analytical perspective—is paramount for designing better policies toward pivotal powers. The study, therefore, does not recommend aligning unquestionably with the priorities of these states, but it concludes that any serious strategy of engagement must take the concerns of pivotal powers seriously.

For all the pivotal powers examined, it is also clear that Europe and the United States should improve their understanding of the interests of these potential partners before approaching them. That will require listening to them.

Further conclusions are:

The “Call to Action on Global Governance Reform” adopted by the G20 in a meeting at the UN provides a solid blueprint for reforms there, at the World Trade Organization, and for International Monetary Fund loan quotas that must be implemented. But blockages at these multilateral institutions, likely to continue under a Trump administration, mean North-South and South-South cooperation in flexible minilateral formats will be the focus of much diplomatic activity and progress. Europe and the United States will have opportunities to achieve goals in minilateral formats, but they may need to improve their understanding of and more easily accept local realities.

To enhance cooperation with pivotal powers on international security, a shift in the European and American mindset is critical. Both need to seriously consider the priorities of the pivotal powers, such as the fight against terrorism or the management of regional conflicts. This implies no public lecturing from the transatlantic partnership on democratic standards or pressuring pivotal powers to choose sides in conflicts that are not of primary concern for them. Following Trump’s reelection, Europe will also have to react to a more transactional US approach to the pivotal powers, which could undermine transatlantic coordination on human rights and democratic values.

To seize the momentum for AI cooperation with pivotal powers, we recommend leveraging the opportunities offered through India and Saudi Arabia on this technology to diversify transatlantic value chains and reduce dependency on China. Despite security concerns, facilitating technology transfers with pivotal powers may also be necessary to mitigate the risk of losing the “New Tech South” to China or Russia.

Policy Recommendations

by Martin Quencez and Rachel Tausendfreund

For the transatlantic partners

-

Change the tone

The US and European approach to pivotal powers is often perceived as moralistic and sanctimonious rather than an engagement among equals. The transatlantic allies must abandon the idea that they know what is in the best interest of other countries. The diplomatic costs of public criticism should be assessed carefully. While this does not mean dropping all references to human rights or universal values, it does mean entering discussions informed about the interlocutor’s perspective and that dialogue behind closed doors is more likely to reach a common understanding than public speeches.

-

Embrace minilateralism

Pivotal powers are engaged in a strategy of multi-alignment to maximize their interests. Transatlantic partners need to strike the right balance between transactionalism and formal alliance-building. Minilateral formats of cooperation, often dedicated to a specific policy issue, are the most promising frameworks for engagement with pivotal powers. But this requires enhancing transatlantic coordination to benefit collectively from existing privileged relationships rather than competing for attention in the “Global South”. And EU-US demands for exclusivity hamper uptake. Transatlantic efforts to develop digital connectivity or clean energy production must happen parallel to Chinese Belt and Road Initiative projects.

-

Improve coordination on de-risking policy

Pivotal powers express great interest in military and technology cooperation with transatlantic partners. While American and European de-risking strategies make sense in theory, they usually appear to others as inconsistent and untransparent. A more coordinated regime to control financial investments, arms sales, and technology transfers to pivotal powers would help leverage these exchanges. As the Trump administration is expected to implement new and stricter trade and technology policies toward China, deconflicting US and EU approaches should be a transatlantic priority.

-

Negotiate joint ventures

The United States and Europe should pursue, using a multistakeholder approach, joint ventures with companies in pivotal powers that build capacity there in clean energy technologies, digital infrastructure, or artificial intelligence. Joint purchasing could be included, if appropriate, as well as co-developing rules and funding. US and EU standards can seep into these efforts but should not be unilaterally imposed at the outset. Capacity building and investment in local manufacturing can support partner countries in their efforts to move up the value chain. This approach would be compatible with the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment or the EU-US Trade and Technology Council.

-

Pursue partnership together and individually

The EU, the United States, and other partners should join forces to create ambitious regional initiatives that aggregate resources. These efforts can combine infrastructure, clean energy, or green technologies with digital infrastructure investment and partnership activities in strategic corridors. The G7’s Just Energy Transition Partnership is a model for collaboration in other sectors. Partners could also coordinate their tackling of different projects in the same region to ensure compatibility.

For the EU

-

Ensure coherence between the Green Deal and the Global Gateway

The EU’s global engagement, as it combines efforts by the bloc and its individual member states, struggles with cohesion problems. Efforts to support EU decarbonization and competitiveness, such as the Emissions Trading System and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, have detrimental effects that run counter to Global Gateway aims. The Global Gateway’s objective should be aligned with the new European Commission’s priorities for competitiveness and decarbonization. Furthermore, the flurry of initiatives (e.g., for energy partnerships and green technology partnerships) should be merged into one effort with a clear strategic vision, perhaps into the Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships, as the European Commission recently proposed.63

-

Maintain a multilateral trade focus

There is pressure to move toward national industrial policy to achieve resilience and a competitive green transition. The World Trade Organization (WTO), however, was not built to address today’s challenges, yet the multilateral system was essential to increasing global prosperity. The EU and its member states should remainstrong advocates of WTO reform and keep this in mind while moving forward with their strategic green agenda. Donald Trump’s reelection, and the prospect of tariffs on all US imports, could offer new opportunities for the EU’s trade relations with pivotal powers.

-

Remember that development policy and human rights are relevant to geopolitics

“Geopolitical Europe” should continue to infuse EU policy areas with more strategic thinking. Development policy and human rights play a traditionally significant role in relations between Europe and many “Global South” actors. The issues cannot be isolated from the geopolitical interests that Europeans rightfully prioritize. Such a separation fosters an impression of hypocrisy and incoherence.