How Could a Context-Sensitive EU Approach Make EAP Societies More Resilient, Fair, and Inclusive?

This blog was written by members of the Policy Designers Network (PDN), a fellowship program that empowers young policy professionals from Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to advance democracy and economic development, to expand their knowledge about regional, European, and transatlantic issues, and to strengthen their networks. During the fellowship, the fellows hone their leadership abilities, strengthen their skills to leverage media to advance policy solutions, to engage stakeholders in advancing their missions, and to write policy papers.

The Eastern Partnership (EaP), the EU’s umbrella initiative toward Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, was launched in 2009. The past year has been an important introspection period for the EU as well as the six countries to assess the progress achieved, recognize the challenges, and propose a more effective way forward. According to its proposal for the long-term policy objectives of the EaP beyond 2020, the EU aspires to design a partnership that—in its words—creates, protects, greens, connects and empowers.

The promotion of democratic values stands at the center of European integration—and of a partnership that empowers. Achieving resilient, fair and inclusive societies in the EaP calls for independent and plural media, active civil society, and the protection and respect of human rights that ensure that no voices are lost or oppressed. Given key differences among the EaP countries, the following paper posits that the EU should adopt a tailored approach to deliver on this objective.

When it comes to media independence and pluralism and the state of the civil society, the six countries have similarities and national differences on both fronts, and the EU has made past and ongoing efforts to address the challenges they face, with varying degrees of success.

Media Pluralism and Independence across the EaP

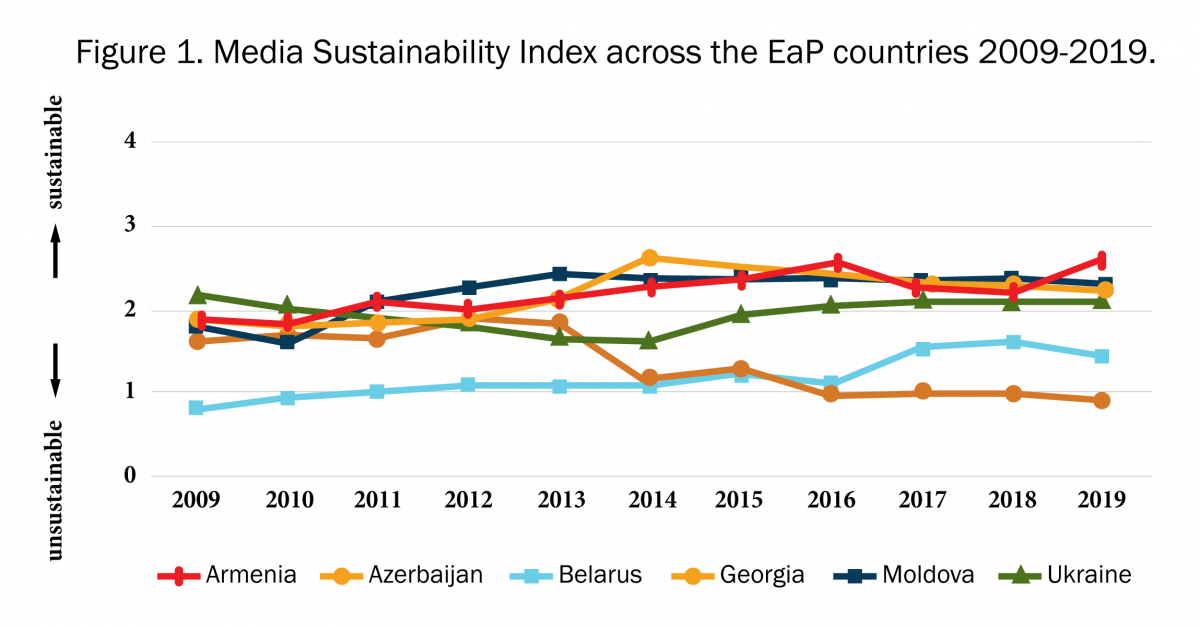

Media pluralism and independence remain shared challenges across the Eastern Partnership countries. According to the Media Sustainability Index (MSI), which measures plurality of news, the state of freedom of speech and supporting institutions in the EaP countries, none of the six countries can be assessed as sustainable (Figure 1). Achieved progress regarding the media independence in all six EaP countries remains volatile towards governmental changes and it mirrors the general democratization dynamics.

Source: IREX. Media Sustainability Index (MSI).

Note: MSI scores range from 0 (low) to 4 (high)

According to Reporters Without Borders, which ranks countries based on an assessment of their legal framework, pluralism, and independence of media, as well as self-censorship, transparency, and infrastructure, the worst performers are Belarus and Azerbaijan, which rank 153rd and 168th out of 180 countries respectively.

The media environment in both countries remains hostile and journalistic rights are frequently violated by persecution, heavy fines, and regime reprisals. Anti-press tactics in Belarus include broad legal restrictions, editorial control, politicized prosecution, and bans on foreign reporters. More than one hundred journalists have been detained for reporting on the anti-governmental protests in Belarus this year. Information landscape, including in online space, is subject to the government's tight grip in Azerbaijan as well. According to the Council of Europe, as of 2020, there are 11 detained journalists and 2 cases of impunity with murder in Azerbaijan. The main independent news websites are blocked. With an aim to silence journalists who continue to resist in exile, the regime harasses their family members still in Azerbaijan. Moreover, the authorities do not hesitate to reach key media actors beyond country borders, getting Azerbaijani journalists arrested even in Georgia and Ukraine.

Armenia is the only EaP country that has progressed considerably in terms of media pluralism in recent years, and it is currently ranked 61st in the world by Reporters Without Borders; Online investigative journalism has also gained prominence to combat systemic corruption. However, the new government has failed to decrease the media’s polarization. Many of the large media outlets engage in selective coverage of the news, serving the interests of their political and financial guardians including the affiliates of the former regime. Additionally, the number of judicial proceedings against professional journalists is alarming and harsh measures undertaken by the National Security Service to combat online disinformation without consultations with the media and civil society representatives require further attention.

Georgia is the highest-ranked EaP country, in the 60th position, but despite the improved pluralism there, the media environment remains highly polarized along the political party lines. Some improvements have been made with regard to media ownership and transparency, however, major media outlets continue to broadcast biased information reflecting their connections to either opposition parties or the ruling Georgian Dream party.

The media environment in Moldova has deteriorated in the past few years, as a result of which it has fallen from the 56th position in 2014 to 91st in 2020. This backsliding is directly related to the country’s political and economic instability, as well as the persisting oligarchic influence over the editorial line of the major media outlets.

Despite the ongoing conflict in the eastern part of the country, Ukraine is currently ranked 96th, having made slight progress regarding media ownership and transparency. However, the media environment in Crimea and Donbas has deteriorated. More than 50 journalists and seven editors have been forced to flee these regions as they faced violence and prosecution.

These national media environments reflect the general democratic and human rights situation in the EaP countries. Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, which have signed Association Agreements with the EU, have made progress in improving their legislative frameworks in line with EU standards. The Velvet Revolution in 2018 also led to greater media pluralism in Armenia. The challenges facing independent media in Azerbaijan and Belarus reflect the bigger issues of having autocratic regimes. However, one challenge for the media in all six countries is increasing disinformation and propaganda. Countering disinformation is only possible by having highly professional journalists and proper media literacy in the wider society.

Civil Society Sustainability and Engagement

Civil society is a crucial dimension of the EU’s approach to the EaP countries. It was listed as one of the key cross-cutting goals in the agenda developed in 2017 for the EaP (the 20 Deliverables by 2020). Furthermore, civil society organizations (CSOs) are expected to play a key role in the EU’s future relationship with the six countries as it is part of Key Post 2020 EaP Deliverables.

However, the EU’s efforts to strengthen CSOs have delivered different results in different EaP countries (Table 1). Since the launch of the initiative in 2009, Armenia, Belarus, and Ukraine have made significant progress. Georgia and Moldova have also made progress in terms of CSO sustainability but qualitatively the progress has been insignificant. As for Azerbaijan, CSO sustainability has been impeded since 2009.

Table 1. Civil Society Organization Sustainability Index in the EaP region

| Overall CSO Sustainability in 2009 | Overall CSO Sustainability in 2019 | Assessment | |

| Armenia | 4.0 | 3.6 | progress |

| Azerbaijan | 4.7 | 5.9 | regress |

| Belarus | 5.9 | 5.5 | progress |

| Georgia | 4.2 | 4.0 | progress (but qualitatively limited change) |

| Moldova | 4.3 | 3.8 | progress (but qualitatively limited change) |

| Ukraine | 3.5 | 3.2 | progress |

Source: https://csosi.org/?region=EUROPE

Note: CSO Sustainability scores range from 1 (high) to 7 (low).

Not only has the progress been dissimilar in terms of CSO sustainability, but the EaP countries face qualitatively different challenges as well. In Armenia and Ukraine, financial viability remains the most pressing problem. While financial viability is a problem in Georgia and Moldova too, these two countries experience other noteworthy challenges such as CSO’s limited impact on policy and the government discrediting them (and as a result deteriorated public image). As for Azerbaijan and Belarus, the primary problem, ahead of these other ones, is the fact that the legal environment remains to be very restrictive.

The EU’s Approach to Promote Media Pluralism

Since the launch of the EaP, the EU has spent more than €30 million in support of media freedom in the six countries. While relative success has been achieved in Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, these states are still ranked as “partially free.” This modest success is a confirmation that ongoing efforts are either insufficient or need more time to produce lasting results. The case of Moldova also demonstrates that progress achieved can easily be lost due to political instability and inconsistent approaches.

The Association Agreements that Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine signed streamline the legal approximation process in various areas, including the media environment. The establishment of the Eastern Partnership Media Conference in 2015, bringing together hundreds of media professionals from the EaP countries and EU member states, is a positive step to identify the regional challenges and exchange best practices. Through the Open Media Hub and European Endowment for Democracy, the EU has supported emerging media outlets, provided financial and technical assistance, and invested in training and networking media professionals in the EaP countries. The EU has also invested in media literacy programs to counter increased disinformation and propaganda.

The EU’s Undifferentiated Approach to Civil Society Empowerment

Considering the differing predicaments and progress of EaP countries in terms of civil society engagement and sustainability, the EU’s approach has been and is expected to remain undifferentiated. The EaP policy beyond 2020 does not seem to discriminate between countries with distinct challenges. Major objectives for the future of the EaP countries in terms of civil society are formulated in general terms and are fundamentally a continuation of the EU’s existing overarching policy towards the EaP as a whole. As a result of this uniform approach, the varied obstacles and needs of different EaP countries are being shoehorned into an overarching policy.

How Should the EU Engage with the EaP Countries More Effectively?

The media environments in the EaP countries differ considerably. Despite the common trends, the differences among them in general political processes, level of democratization, and human rights situation indicate the need for a more tailored approach from international partners. The EU should take a proactive approach to address the national characteristics of each EaP country, taking into account the local contexts of the media environment. Its efforts should include complementary programs that ensure media plurality by removing legislative barriers, promoting higher professional standards of neutrality and objectivity, supporting the diversification of media actors, including the regional and local media outlets providing accessible information to all societal groups, and building up investigative journalistic skills and turning the media into a reliable watchdog that effectively keeps the government accountable.

In order to meet the different challenges of EaP countries in terms of civil society engagement and sustainability, it would be more efficient if the EU would define subgroups of EaP countries and address their specific problems.

One group could be comprised of Armenia, Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, where the legal environment is largely friendly to CSOs but they struggle in terms of financial viability. When collaborating with the governments of these countries, the EU could use conditionality to ensure that CSOs have a realistic opportunity to attract local sources of funding. Moreover, in each of these four countries, there is a narrow circle of well-established CSOs that get most of the EU funds. Even though these do a great job, the EU should diversify its funding and support more diverse civic groups.

Georgia and Moldova could also perhaps form a subgroup of their own as CSOs there have been experiencing waves of discrediting by the government, which has led to their deteriorating image. The EU could effectively demand from the Georgian and Moldovan governments to stop this practice.

Belarus and Azerbaijan would form another subgroup. In these countries, CSO sustainability and engagement is largely embedded. Most importantly, the legal environment, which can be considered as a precondition of a functioning civic sector, remains fundamentally restrictive and the EU should try to focus on improving it in the first place. CSOs in Azerbaijan experience constraints on their operations and are subject to significant obstacles when registering. The legislation in Belarus bans activities of some organizations and contains contradictory norms regarding functioning of CSOs.

Recommendations Regarding the Media Environment

The cases of Azerbaijan and Belarus demonstrate that media freedom is just one aspect of the general human rights situation in any EaP country. Therefore, the EU should approach media issues in conjunction with the protection of human rights.

The independence of the media is not a distinctively Eastern European challenge and a number of EU countries face similar problems. Therefore, the EU should continue to promote an exchange of best practices between EU and EaP media platforms.

Existing fact-checking efforts should be extended to the wider media-literacy programs that are part of educational programs.

The EU should also make sure that supported emerging media outlets develop a sustainable business model that will act as the basis for future financial stability.

Recommendations Regarding Civil Society Sustainability and Engagement

With Armenia, Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, the EU should adopt a tailored approach to ensure the financial viability of CSOs.

EU funds should focus more on regional CSOs in order to balance “elite/cartel” NGOs.

When collaborating with governments, the EU should place a condition that CSOs have a realistic opportunity to attract local sources of funding.

The EU should adopt a bottom-up approach when it comes to setting its funding priorities (instead of a top-down one-fits-all approach).

The EU should also demand clearly from the Georgian and Moldovan governments that they stop discrediting CSOs.

With Azerbaijan and Belarus, the EU should focus more on improving the legal environment for operating CSOs.