On Electoral Reforms, Germany Chooses Against its Own Constitution

The Council of the European Union, and more specifically the German governing parties, have once again fielded a proposal to introduce electoral thresholds in the European Parliament elections across member states. These thresholds are meant to keep parties that receive less than 2 to 5 percent of the total vote in any constituency with more than 35 seats out of the “hemicycle.” An argument in favor of these limits is that they prevent an excessive fragmentation of the parliament, which makes the formation of coalitions and issue-alliances easier and prevents fringe parties from receiving public funding. A counter-argument might be that votes for parties that do not make the cut are essentially wasted and thus not represented in parliament — a clear advantage for the larger parties that then get to occupy the seats corresponding to these votes.

There are a couple of reasons to take issue with this. The obvious one is that similar attempts have been made ahead of the EP elections of 2014 and 1979 by previous German governments. Both attempts failed because the German constitutional court decided in 2011 and again in 2014 that such an electoral threshold was a breach of equal voting rights and thus, of the German constitution. In short, its judges were convinced by the argument that thresholds advantage larger parties, though by a slim margin.

Furthermore, it is unlikely that this law would even take effect in the upcoming EP elections. The proposal is now envisioned to be fully implemented in time for the 2024 elections. The Council Presidency has already announced that an implementation in 2019 would violate the code of ethics prohibiting changes in the electoral law less than 12 months prior to elections. And, once more, the law would still have to survive the constitutional court of Germany, to which it would unfailingly be dragged after the German government implements the law. Finally, there is no obvious reason to pass legislation on something that will only become relevant in 2024 now, when there is still plenty of time for changing circumstances.

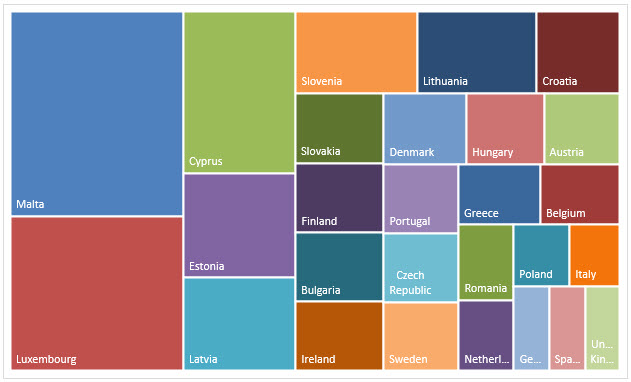

The German Constitutional Court’s previous rejections of thresholds are interesting in that firstly, thresholds have not been revoked in German elections;[1] and secondly, the European Parliament is not elected on the basis of the “one (wo)man, one vote” principle that is often used to describe equal voting rights (see graph below). In fact, the principle could more aptly be named “one (wo)man, between one and ten votes.” This is due to minority protection, meaning smaller member states are overrepresented and larger ones underrepresented in a system referred to as “degressive proportionality”. However, the actual seat share per country in the current parliament was subject to political bargaining rather than a neutral mathematical formula. And no matter its noble origins, the system certainly does not give equal representation to all citizens. There are thus arguably greater obstacles to equal voting rights in the EU than the representation of small parties in parliament and the German constitutional court’s decision may not be completely unequivocal.

However, the reasoning behind it was very clear: in European elections, which do not produce a government requiring a stable majority in parliament, voter equality is more important than the efficacy of parliamentary alliances and decision-making. Given that this has not changed there is no reason to hope for a different outcome this time.

What is more, Germany’s government is not only backing a loser, it rejected a winner. Berlin could have supported a reform to European electoral rules that would be approved by Karlsruhe: the transnational party lists.

Transnational lists, as they were suggested in a proposal both fielded and rejected mainly by the European Peoples’ Party in the European Parliament, would have granted around 40 seats of the new parliament to candidates elected through European a lists. Transnational lists would effectively have made the EU one constituency and every vote count exactly the same — all European citizens eligible to vote would have picked their favorite party’s list. Imagine a system like the Dutch general elections, but at a European level: Each European or national party submits its list of candidates, all of which then compete in the same “electoral district,” the entire EU. The seats for each party list are then apportioned proportionally to the vote-share received by each party. The better the party fares, the more people from its list will get a seat, starting from the top. Unlike the current system, this could mean that voters in Spain give their vote to a Greek, a Slovak and a Danish candidate. The MEPs chosen through a transnational list would have inherited around 40 of the the 73 vacant U.K. seats, meaning that there would not have been a breach of the standards of minority protection, either — they would simply have been added to the nationally apportioned seats. A small step toward more voter equality in Europe, but a step nonetheless. This initiative would clearly have moved the electoral procedures for the EP closer to what the twice confirmed interpretation of the German constitution would suggest is more democratic than the status quo — equal weight for every vote across the EU.

Yet, the largest German party in government rejected the proposal, and the government did not support it. This government has declared the EU one of its key priorities. Yet, at a time when the EU could clearly use a positive break, the CDU/SPD government chose to use its fading political capital in Brussels to once more launch an attempt to introduce thresholds that are deemed unconstitutional in Germany.

One can only hope that, regardless of partisanship or opportunities of the past, the German parties do not display such a cavalier attitude toward European democracy during their campaigns — by making them about actual European policies, by mobilizing more than just half of the electorate, and by not wasting their political capital in Brussels on futile initiatives in the future.

How much MEP each inhabitant gets for their vote: a graphical representation based on current seat apportionment in the EP.

[1] This was based on the observation that a the European Parliament does not need a threshold to be able to form a functioning government, whereas the German parliament does: http://www.bpb.de/politik/hintergrund-aktuell/179547/urteil-zur-drei-prozent-sperrklausel-25-02-2014