Building Resilient, Sustainable, and Integrated Economies in the Eastern Partnership Countries

This blog was written by members of the Policy Designers Network (PDN), a fellowship program that empowers young policy professionals from Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to advance democracy and economic development, to expand their knowledge about regional, European, and transatlantic issues, and to strengthen their networks. During the fellowship, the fellows hone their leadership abilities, strengthen their skills to leverage media to advance policy solutions, to engage stakeholders in advancing their missions, and to write policy papers.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, all the post-Soviet countries faced a similar set of challenges, including a loss of economic relations and markets. The need to move to a market economy resulted in transitional chaos and the dissolution of economic and state structures. Institutional collapse resulted in the mass spread of corruption, and many post-Soviet countries descended into poverty. Consequently, it is not a surprise that many people started to emigrate to wealthier countries in pursuit of better opportunities. After gaining independence, differences between regulatory frameworks and incoherent responses to crisis led to an economic and political divergence among these countries, which also contributed to a breakdown of economic links among them.

The problems that the post-Soviet countries face vary from politics and the economy, to war and ethnic conflicts. Some of the regimes over which the Kremlin has managed to exert a significant influence in its attempt to sustain “controllable chaos” still have to struggle with internal conflicts and war. Additionally, some post-Soviet countries now have closer relations with the EU than others.

Since the late 1990s, the EU gradually started to get involved with these countries and offered them preferential trade arrangements under the Generalized System of Preferences and Autonomous Preferences to lay the groundwork for deeper cooperation with them. The Eastern Partnership (EaP) policy was adopted in 2009 to support Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine in transforming their political, social, and economic systems. However, progress in cooperation with the EU varies among the EaP countries due to the differences in their political systems as well as their economic and social problems. But, despite these differences, there are also common challenges and potential solutions for the EaP countries in building sustainable and resilient economies.

The Geopolitical Situation

The EU has moved further ahead in support of the EaP countries’ democratic and economic development. Currently, three of them have a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the EU. Georgia and Moldova signed theirs in 2014, and Ukraine in 2016. These countries have expressed their strong commitment to integration with the EU. However, in their efforts to achieve more robust convergence with EU institutions, these three countries have had to pay a high political and economic price since such moves conflicted with Russian interests in the region. Alongside the exacerbation of conflicts and domestic destabilization, trade restrictions became a standard mode of conduct for the Russian government. For example, Ukraine’s foreign trade suffered from Russian sanctions in 2018– 2019, while in the case of Moldova, Russia used technical criteria to restrict the export of its agri-food products. Georgia also experienced a significant economic downturn in 2006 when Russia put an embargo on its products. Georgian-Russian relations did reach a point of normalization after 2013, but political tensions still escalate from time to time.

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus have relatively weaker cooperation with the EU, for different reasons. The EU is the second-largest trade partner for Belarus, with around 18 percent of its overall trade in goods and services. Even though the EU is one of the major markets for Belarus, the lack of democracy in the country hinders building more robust economic and political ties with the EU. The EU has repeatedly suspended cooperation with Belarus due to a lack of improvement in political and civil conditions.

Armenia has achieved little progress in economic and political integration with the EU. As a result of Russia’s political manipulation of natural gas prices and of arms deals, Armenia refused to sign a DCFTA with the EU in 2013. Instead, it joined the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). However, this ended up being quite costly for the country. It was forced to align its import tariffs to the higher EAEU rates, resulting in price hikes for imported goods.

The relationship between Azerbaijan and the EU is a unique case among the EaP countries. Due to its oil and natural gas reserves, the country is able to leverage its importance for the EU while remaining free from Russian influence. Azerbaijan prefers to run an independent policy and hesitates to make commitments that could undermine its political system. Therefore, relations with the EU currently are limited to economic cooperation, and no further expansion is expected in the near future. The EU and Azerbaijan trade under the most-favored nation regime, which was granted to the country even though it is not a member of the World Trade Organization, in which it has only observer status only.

Economic Challenges

The barriers hindering economic development in the EaP countries include poor quality of state institutions, low technological development, absence of high-value-added domestic production, low energy efficiency, dependence on imported energy resources for processing raw materials, government subsidies, and lack of transparency. The low performance of state institutions inhibits the formation of a transparent and competitive business environment, which itself restricts investment in economic activity and job creation.

Without proper knowledge and political will, the post-Soviet transformation was largely predestined to fail for some countries. Economic turmoil was primarily caused by the unpreparedness of local elites to face the newly established economic order, combined with an attempt to sustain social guarantees and governance mechanisms that existed during the Soviet Union, but without access to the same resources. Furthermore, the legacy of Soviet bureaucracy proved to be fertile soil for corruption.

Corruption and economic blunders are the reason why 29 years later some post-Soviet countries still struggle with high poverty rates and wealth inequality. Corruption and lack of transparency and fair competition in the process of privatization meant that land, assets, and wealth were grabbed through corrupt practices by a small, privileged portion society affiliated with political elites.

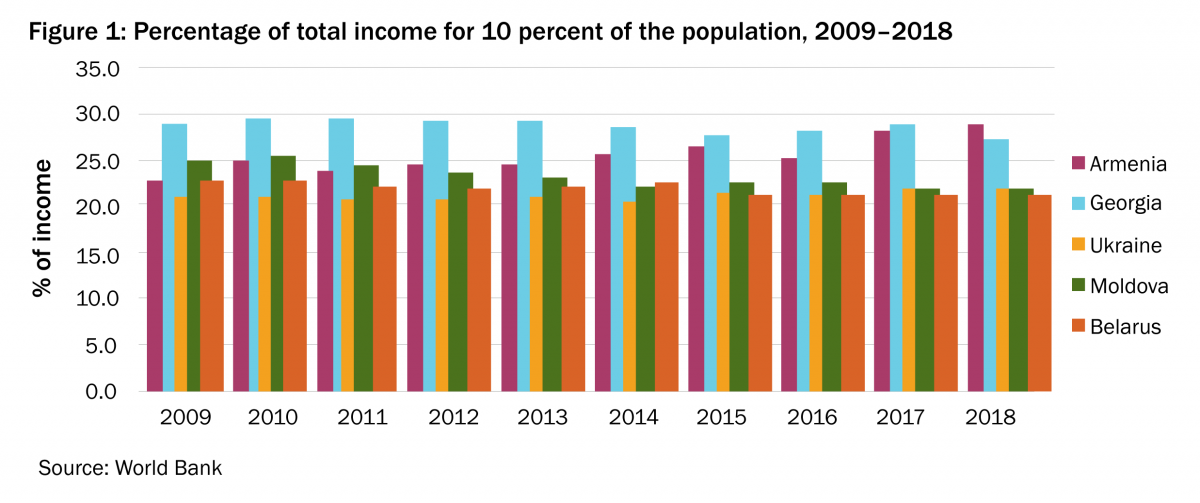

Income disparity is visible in all EP countries. According to the World Bank, the top 10 percent of the population accounts for 20–30 percent of total income in the EaP countries (Figure 1). Meanwhile, the bottom 10 percent are left with less than 5 percent of it.

Large income discrepancy among different parts of society results in high poverty rates, limiting people’s access to proper education and medical services, which in turn results in limited skills development and economic growth.

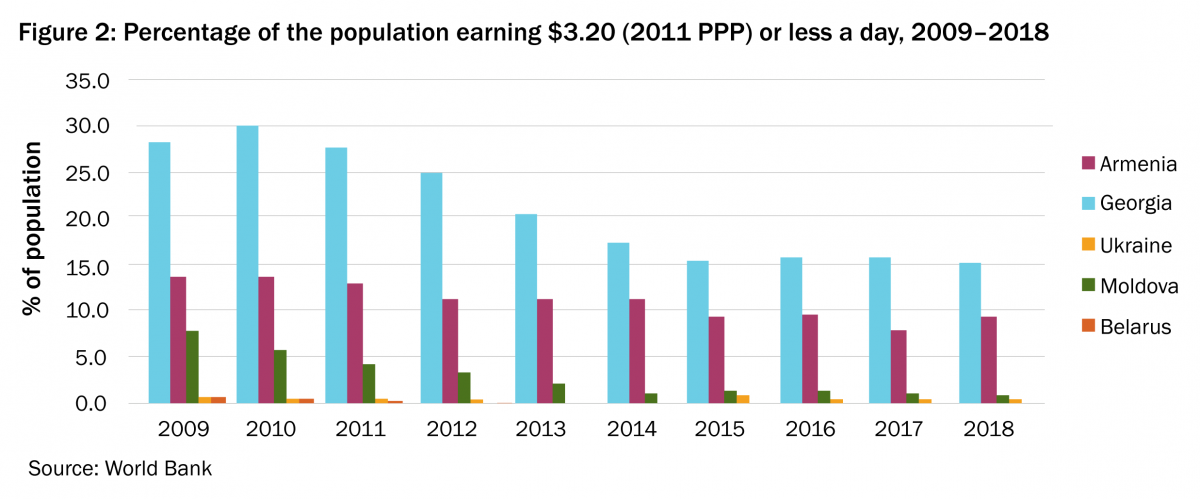

Even though the poverty rate has been going steadily down in all EaP countries except Ukraine, it remains significantly high in Armenia and Georgia (Figure 2). The World Bank data does not include Azerbaijan, indicating a lack of transparency in the country.

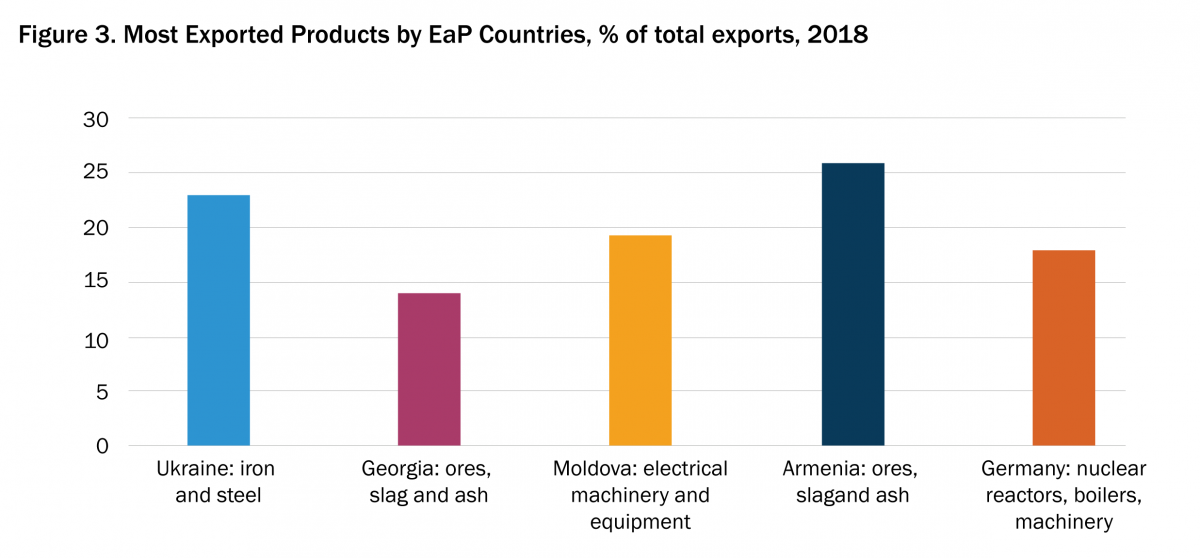

Low competitiveness of domestic producers is also among the common challenges faced by EaP countries. Notwithstanding the cooperation and free trade arrangements with the EU, most of them still cannot compete in the European market. Governments decided to prop up the industries they inherited from the Soviet past to prevent them from failing. Meanwhile, little effort was made to develop new technologies and high-value-added production. Even today, most of the EaP countries still focus on raw materials and primary products with a small share of value-added. For example, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, in 2018 Ukraine’s main export items were seed oils, semi-finished iron, corn, wheat, and iron ore. Georgia exported ferroalloys, fertilizers, nuts, scrap metal, gold, copper ore. Moldova exported wire, sunflower seeds, and hot-rolled iron bars. Armenia exported copper ore, gold, rolled tobacco, ferroalloys, and hard liquor. Figure 3 shows the most significant share of exported products by countries.

Conclusion

Despite the differences between the EaP countries, some areas do exist where a standard approach can be taken by all. Even though their respective socio-political orders differ, their level of economic development is more or less similar. According to the World Bank, all have a per capita GDP of $3,000–9,000. According to the World Economic Forum, countries in this category should invest in higher education and training, facilitating efficient labor markets, and more robust financial institutions. This will increase the availability of a large pool of skilled workers as well as improve innovation and infrastructure, ultimately leading to more efficient production processes and increased product quality.

Accelerated economic growth is vital for creating more efficient social policies and welfare reforms to reduce poverty and competitiveness of national production. For this purpose, the EaP countries should use all available opportunities to stimulate their economy, improve national production competitiveness, and pave the way to the international markets.

As stated above, human-resource development and up-skilling of the workforce should a priority for all EaP countries. This will help them to reorient their economies from primarily service provision and primary-production to more high-value-added production and manufacturing. Combined with higher education, internships and placement programs can play a crucial role in providing on-the-job training for recent graduates.

However, the policy should go beyond higher education. There should be mechanisms to incentivize all stakeholders to initiate training and educational programs for unskilled workers. For example, a tripartite system can be proposed, whereby the state, workers’ unions, and employers (or employers associations) come together and share responsibilities and costs to up-skill the workforce. The government and employers can initially share the cost of such training, while the beneficiary workers will take deductions from their salaries for a limited period of time (or while they are undergoing the training) to cover for their share of the training cost. This way, the burden on employers is minimized, making it more worthy of taking on risks associated with poaching of employees (due to new skills being transferrable) or rapidly changing technologies.

Additionally, more effort has to be put into promoting engineering, chemistry, IT, and energy to create innovation. Cooperation between universities and research centers, producers, and manufacturers should be encouraged and stimulated, possibly by offering tax exemptions, especially for investment in research and development. Cooperation between universities and enterprises helps stir innovation and development of new products as well as creating more demand for science and technology. Such cooperation facilitates establishing educational, research, and industrial hubs such as technology parks.

Furthermore, the EaP countries must strengthen their existing economic ties to facilitate trade and gain access to the international market. Hence, considering their deeper integration into the Euro-Atlantic systems of governance, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine need to follow the accession agenda and support the transformation of domestic institutions and development of a regulatory framework to create an environment conducive to foreign direct investment. Particular attention should be paid to introducing national quality and food-safety standards to penetrate non-tariff trade barriers in the EU market. Also, in addition to the improved regulatory framework, capacity-development opportunities should be offered to local export-oriented industries to facilitate the adoption of quality standards, strengthen the competitiveness of domestic production, and increase trade.