Italy’s Future in the Eurozone

Further troubles for the euro area loom ahead. On Sunday, December 4, with a simple yes or no vote, the Italian people will decide not only over a constitutional referendum but also about their country’s future in the euro area. If the referendum passes, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, who has bet his career on a yes, could end the deadlock in Italy’s bicameral system by reducing the size of the senate and proceed to enact much needed structural reforms. However, the latest polls suggest he will lose, with 42 percent saying they will vote no, 37 percent yes, and 21 percent undecided.

The unpopularity of Renzi’s proposals might be traced back to their flawed design and doubts about them bringing about real improvements. But the problem may also be that the prime minister has not been able to show any political wins against the austerity politics of Brussels and Berlin that would have made his campaign narrative of reforming Italy and pursuing more European convergence more appealing. Despite Italy's unfolding banking crisis, massive capital outflows, and GDP still running almost eight percentage points below its pre-crisis level, euro-area governments such as Germany’s have repeatedly spoken out against Mr. Renzi's demands to relax agreed-upon deficit targets. Considering what is at risk now, substantial concessions to Italy should have been made. And while they would come too late for Renzi and Sunday’s results, they still should be made before the worst-case and possibly self-fulfilling scenario manifests itself and the country heads for Exitaly. Although the probability of this scenario is disputed, its consequences would certainly be graver than Brexit.

Commentators have identified four possible scenarios. First, after a tight loss Renzi will resign and a technocratic caretaker government will take over until elections in 2018. Second, President Sergio Mattarella rejects Renzi’s resignation or the prime minister retracts from his vow to leave office and finishes his term. Third, a defeat for Renzi by a large margin will likely trigger snap elections in 2017. Fourth, the prime minister actually wins the referendum and continues to push for reforms. As the first scenario seems likeliest, there are several good economic and political reasons why hawkish euro-area governments should consider making substantial concessions to the Italian government after the referendum.

A technocratic caretaker government until 2018 would have to accomplish two major tasks to keep the country off the Exitaly path. In the short run, it would need to minimize and credibly manage the fallout of financial speculations on Italian banks that will follow the referendum. This needs to be done in the context of three very specific problems. First, the extent of private contributions to banks in Italy’s recapitalization scheme creates negative, systemic feedback. Earlier this year, Italy created an investor-financed fund (Atlante) to help distressed banks raise capital and to act as a backstop to shore up confidence in the banking sector, in which non-performing loans account for 14 percent of total loans. However, this construct is unfit to provide a sector-wide or long-term solution should the Italian banking crisis become more acute. It is mostly financed by Italian banks and, by acting as a shareholder of last resort for those banks that are not able to raise capital on the market, it accumulates risk onto the balance sheets of a banking system that is already very interconnected.

Second, spillovers from weaker banks to the rest of the system might be unavoidable. Specifically, a domino effect originating from the disruption of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Sienna’s (MPS) complex €5 billion recapitalization and bad-debt restructuring could translate into a wider failure of confidence in Italy's banks and imperil a market solution for its ailing banks. As many as seven others are known to be in distress and could be heavily affected by a collapse of MPS: mid-sized banks Popolare di Vicenza, Veneto Banca, and Carige, and four small banks rescued in 2015. In the less likely event that worries spread systemically triggering bank-runs, Italy might be forced to ask for a full blown European intervention via the ESM or leave the eurozone.

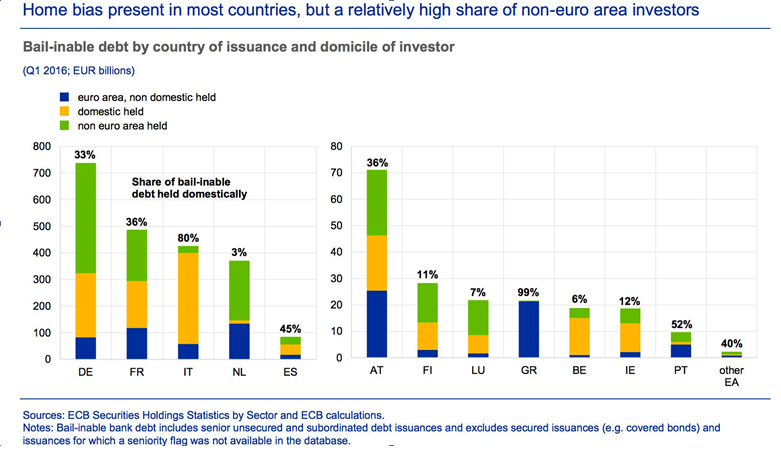

Third, the social and political consequences of bank resolutions and bail-ins according to EU-state-aid rules would be more severe than in other countries. Ill-advised tax incentives and fraudulent mis-selling of bank bonds in the past have significant consequences for the situation that the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) foresees in a case of raising additional capital. A mandatory preliminary bail-in of 8 percent of total liabilities must be implemented before public money can be used. For MPS, the 8 percent bail-in requirement would imply bail-in of all or almost all junior debt (approximately €5 billion). Of the “bail-in-able” Italian debt, 80 percent is held domestically and one-third of bank bonds are held by domestic households.

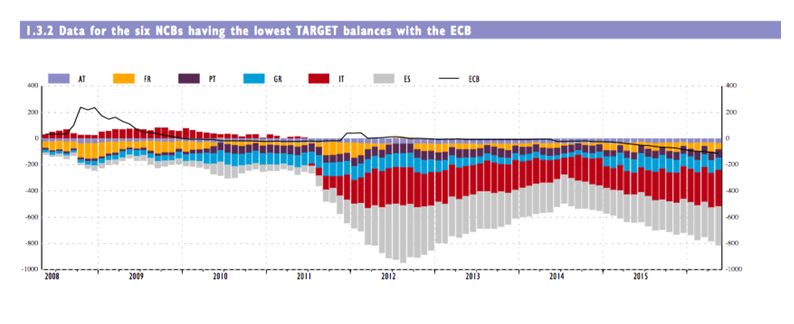

Judging by its Target2 balance, the euro area’s gross settlement system, substantial capital outflows since the beginning of this year herald another balance-of-payment crisis and are an indicator for an intensifying Italian banking crisis. The Bank of Italy's liabilities towards other euro-area central banks hit a new record high of €355.5 billion in October, which equals a deficit of above 20 percent of GDP.

Source: ECB 2016

As the euro area has been muddling through for several years now, all sorts of political variations and compromises are possible that deviate from the procedural rulebook of the fiscal compact and the BRRD. The European Central Bank (ECB) has already indicated that it stands ready to defend Italian government bonds against speculative attacks. However, it should be clear that any deal between the Eurogroup and Italy to bail out Italian banks in the likely case the Atlante fund cannot provide relief will involve even stronger elements of conditionality on behalf of Germany. Should Italy need bank recapitalizations after the referendum, the estimated size of the bail-out of up to €52 billion is higher than anything the Atlante fund could provide and the country will need to turn to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) for direct bank recapitalization. This procedure is lengthy and painful, and it would not only require a reform agenda in accordance with the European Commission and the IMF but also the consent of euro-area parliaments including the German Bundestag. This may in turn increase the popularity of the anti-German and anti-euro populist movements in Italy in the run-up to the elections in 2018. There is a high risk that an interim government in its effort to reach a deal with the Eurogroup would be perceived as a “Monti 2.0” model, i.e. one that has to give into renewed austerity demands by Germany.

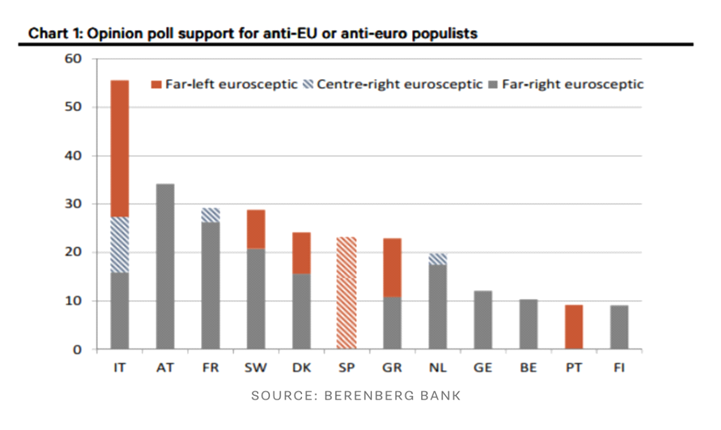

In the medium term, and connected to what’s happening in the short term, a caretaker government should change the electoral law (the Italicum). Originally one of Renzi’s projects to reform the political system, it entered into force in July and is currently under review by the constitutional court. The Italicum changes the electoral law for the lower house from a proportional system to a “winner takes all” system. The concentration of power this could produce might be problematic considering Italy's current political dynamic. Should the Five Star Movement come first in the 2018 elections and form a coalition with other Eurosceptic parties (Italy has the largest Eurosceptic camp of all euro-area countries), it could attain a stable majority without winning a majority of the votes. This is because the Italicum attributes 340 premium seats out of the total of 630 in the lower house to the party winning at least 40 percent of the votes.

Italy: Lega Nord, FdI, Forza Italia (striped), Five Stars; Austria: FPÖ; France: Front National, DLF (striped);

Denmark: DPP, Red-greens; Sweden: Sweden Democrats, Left Party; Netherlands: PVV, SGP (striped);

Greece: Golden Dawn, LAEN, EE, KKE, PE; Spain: Unidos Podemos (striped); Germany: AfD; Belgium: Vlaams

Belang; Portugal: BE; Finland: PS; relevant parties only; average of last five polls; striped means position

somewhat unclear. Source: national opinion polls, Wikipedia, Berenberg calculations.

In addition, with monetary policy having run its course, fiscal policy seems to be the only thing left in governments’ toolbox. Lower interest rates and quantitative easing were explicitly intended to buy time for households, the financial sector, and sovereigns to repair their balance sheets and enact growth-enhancing policies. In the long run, extensive monetary easing is doing more harm than good as central banks all over the world have engaged in a race to the bottom while trying to contain capital outflow volatility, investors are being pushed into riskier asset classes and increase their leverage exposure on their search for yields, and savers lose money as banks pass on the incurred costs of negative interest rates. In addition, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s promise of massive fiscal stimulus might eventually force the U.S. Federal Reserve to raise its rates more quickly and will increase the pressure on the euro area to stimulate aggregate demand and address low productivity by fiscal expansion. Otherwise, Europe had a difficult choice to make between accepting either destabilizing capital outflows or a rate rise that could end the euro area's weak recovery entirely.

Hawkish euro area member states, foremost Germany, are gambling big on Italy neither falling into populist chaos nor into severe financial trouble that could lead to it leaving the euro area. For this gamble to hold, Renzi must win the referendum or, failing that, a caretaker government will have to prevent financial collapse in the short term and reform the electoral law before 2018. In this context, eurohawks may have miscalculated or underestimated three risks. First, the importance of political risk for financial stability in the euro area is still far greater than assumed. Second, the time the ECB could buy for member states to identify the key structural flaws of the currency union and reform them is shorter than expected. And third, the probability of an anti-German, anti-euro populist camp rising to power in Italian politics that will get a referendum on the euro underway after winning the elections in 2018 is greater than expected. As a fourth point, eurohawks might also underestimate what Exitaly will mean for the future of the euro area and their own economies.

The outlook is bleak. What might have been prevented with a more cooperative approach towards Matteo Renzi’s demands by the Eurogroup 12 months ago will now certainly cost a lot more for Italy, Germany, and the euro area as a whole.

In any case, Italy should be allowed precautionary recapitalizations of banks. The new BRRD-framework should be followed and junior bondholders should be bailed-in with the Italian state reimbursing retail investors who fell victim of bad business practices. This as well as a sizeable increase of Atlante's asset capacity to act as a bad bank for the entire sector will need to at least in part come out of Italy's federal budget. The supervision of the implementation of a holistic transition strategy for the banking sector should be taken over by the European Commission.

Germany and other hawks should re-evaluate their stance on Italy, and they should tread lightly when the ultima ratio of bank recapitalization via the ESM is considered and when it comes to conditionality. A stand-off like the one with Greece would certainly drive the Italian banking sector to the brink of collapse. But even if capital shortfalls and speculative attacks can be contained, the populist path to Exitaly could be set now by eurohawks running the show as they are used to — with the belief that the current approach is without alternative and that tough conditionality will eventually benefit at least the majority of euro area member states.

Photo credit: Pava