Massive Russian Financial Flows Through Moldova Show Small Jurisdictions Matter

In 2014 the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) revealed a staggering Russian money-laundering operation perpetrated through Moldindconbank in Moldova, alternatively dubbed the Russian Laundromat[1] or the Global Laundromat.[2] Financial facilitators allegedly moved $20 billion from Russian banks to Moldindconbank over five years, where they “cleaned” the money using Moldovan court orders backing fraudulent claims that borrowers had defaulted on promissory notes. They then moved the proceeds to banks in Latvia and around the world. According to the OCCRP, Moldindconbank received $20 billion in potentially illicit inflows—a truly colossal sum for one small institution in one small country.

Yet the real amount of Russian money that was laundered in Moldova through Moldindconbank or through other institutions during this period is very likely much higher. In 2017 The Guardian reported that Moldovan law-enforcement officials “believe the real total may be as high as $80 billion.”[3] Our analysis of data in the 2016 Statistical Yearbook of the National Bank of Moldova (NBM) shows that the amount of Russian money that entered the country’s banks between 2010 and 2014 was approximately $75 billion.

All this points to the inadequate response by Moldova’s government in the face of the staggering scale of the problem, to the possibility that similar illicit activity also occurred at other Moldovan banks, and to the importance of tracking cross-border payments. Most of all, the Moldovan experience shows that small jurisdictions matter, and that solutions must be comprehensive if they are to be enduring.

Absent such solutions, private Russian actors and the Russian government will continue to exploit weak links in the Western financial system to conduct malign financial activity. In so doing, they will be able to export corruption, clean criminal proceeds, and facilitate interference operations.

Up to $70 Billion in Potentially Illicit Funds

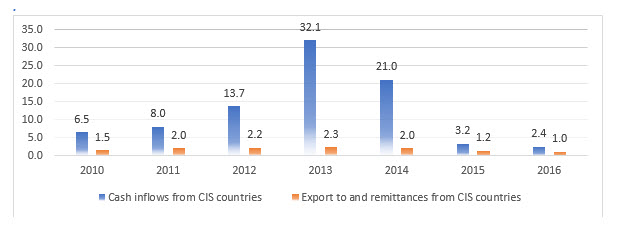

NBM statistics show a large increase in inflows from Russia in 2010-2014, followed by a sharp drop-off in 2015-2016, after the extensive negative press coverage of the Laundromat revelations. Total 2010-2014 inflows from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) were $80 billion, with $75 billion from Russia.[4] Inflows reflecting real economic activity with CIS countries probably amounted to not much more than $2 billion per year, consisting primarily of payments for trade and remittances (foreign direct investment and external financing from Russia, although minimal, may also have contributed slightly). Inflows in 2015 and 2016 averaged about $3 billion per year, reinforcing this estimate. Therefore, subtracting “economic” flows of $10 billion from total flows of $80 billion in this five-year period indicates that “excess” or potentially illicit flows from the CIS into Moldova may have been as much as $70 billion (see Figure 1.), or almost 10 times the GDP of the country.[5]

Figure 1. Cross-border inflows vs. economic activity with CIS countries, USD billions.

Source: 2016 Statistical Yearbook, National Bank of Moldova, “International accounts of Moldova,” p.77, and the 2014 yearbook, p.59.

How the Laundromat Worked

In order to move $20 billion out of Russia, facilitators created at least 21 shell companies registered in the United Kingdom, Cyprus, and New Zealand. A shell company “borrower” issued a promissory note to a second shell company masquerading as a “lender,” thus fabricating a debt.[6] Moldovan citizens endorsed these notes on behalf of Russian companies. The “borrower” then defaulted and the facilitators used the Moldovan courts to enforce the fake debts. They did so by obtaining court orders requiring the Russian companies to repay the “lender.” Since neither side contested the debt, the orders were issued within five days of application. The Russian companies then wired the money into Moldindconbank accounts maintained by a court-appointed executor. Once the funds were received at the bank, they were wired to the accounts of the “lenders” at Trasta Komercbanka in Latvia and then onward. According to the OCCRP, such funds went to 5,140 companies in 96 countries.[7]

Among the beneficiaries of the enormous sums behind the Russian Laundromat was Alexey Krapivin, the son of a deceased associate of Vladimir Yakunin—the former president of Russian Railways. Between 2011 and 2014 Krapivin’s firms allegedly received at least $277 million from the Laundromat, according to OCCRP.[8] In 2012 and 2013, companies controlled by the Krapivin family and its partners won contracts worth $3.7 billion from Russian Railways.[9]

Another beneficiary was the Moldovan banker Ilan Shor. Between 2011 and 2013, his companies allegedly received about $22 million from the Laundromat shell companies.[10] He was convicted in 2017 for his role in a $1 billion bank fraud in Moldova but is under house arrest pending appeal. He won a seat in the parliament in February’s elections.[11]

Moldindconbank was controlled at the time by Veaceslav Platon, a former member of parliament who was convicted of financial crimes in Moldova and sentenced to 18 years in prison in 2018. At least 19 banks served as sources of the funds on the Russian side, most prominently Russian Land Bank (RZB), which allegedly remitted nearly $10 billion.[12] RZB was allegedly controlled by Alexander Grigoriev, who was arrested by Russia’s Federal Security Service in 2015 for allegedly laundering $46 billion through Moldovan and Baltic financial institutions.[13] Igor Putin, the cousin of President Vladimir Putin, served on RZB’s board of directors until 2014.[14] He was also a board member of Promsberbank, which was implicated in money-laundering scandals at Deutsche Bank and Danske Bank.[15]

Moldova’s Handling of the Laundromat

Moldova’s authorities failed to act in a meaningful way in the face of what was obviously a major problem. When a court examined a debt-repayment claim based, for example, on a promissory note between two offshore shell companies worth $700 million (about 10 percent of Moldova’s GDP in 2014) and endorsed by a Moldovan citizen and a Russian company, it should have noticed a red flag. When such cases happened continuously and involved billions of dollars, it was obvious that an industrial-scale operation was taking place to launder money from Russia into the Western financial system.

The perpetrators were able to exploit shortcomings in legislation, as well as the impact of the nexus between money and politics had on the Moldova’s supervisory and prosecution authorities.[16]

The country’s judges are not legally charged with determining whether suspicious transactions relate to money laundering. This is the competence of the financial intelligence unit. Furthermore, the Penal Code states that a criminal investigation on money laundering can only be initiated if the origin of money is proven to be illicit. In other words, a decision by a Russian court would have been needed to conduct investigations in Moldova on suspicious Laundromat transactions.

What is more, in 2010–2011 the parliament and Constitutional Court approved several changes to the legal framework that paved the way for the Laundromat. Most importantly, the parliament approved a law capping at 3 percent the tax for the examination of debt-recovery claims, setting a threshold of $2,000 for individuals and $4,000 for legal entities.[17] The amendment decreased the costs of operating the Laundromat. The author of the bill was Alexandru Tanase, who later was a member of the Constitutional Court until 2017.[18]

Between 2010 and 2014 Moldova’s financial intelligence unit, which is independent from the NBM and has primary anti-money laundering (AML) responsibility, fined Moldindconbank $250,000 for failure to report suspicious activity. The NBM—the country’s banking supervisor—has disclosed only that it issued 18 fines to unnamed banks between 2010 and 2015, without mentioning if Moldindconbank had violated its AML obligations. It could certainly have done more. For example, it has the ability to block suspicious transactions, impose special administration on a poorly governed bank, or block the acquisition of stakes in banks by suspicious shareholders.

What made the Laundromat scheme particularly ingenious is that Moldindconbank was not legally allowed to refuse to execute a transfer mandated by a court order. However, this did not oblige it to continue to onboard and service a group of customers transferring billions of dollars on the basis of remarkably similar, and dubious, promissory notes. The bank further protected itself by filing suspicious activity reports to the financial intelligence unit.[19]

In May 2014, The Supreme Council of Magistracy conducted an assessment of the court orders that legitimized the billions in fake debts.[20] However, criminal proceedings were delayed until September 2016 and then further postponed.[21] Neither the judges who issued the dubious court orders nor Moldindconbank officials were ever sentenced. Prosecutor General Corneliu Gurin, who declined to pursue those cases aggressively, has since been appointed to the Constitutional Court.

The political environment in Moldova changed earlier this year when a new government took office. This may herald a break with the conditions in the country that made corrupt schemes like the Laundromat possible.

Lessons Learned

The scale of the problem revealed by the uncovering of the Laundromat scheme and by the analysis of Moldova’s official statistics underscores the importance of the proactive analysis of cross-border flows by financial intelligence units, supervisors, and law enforcement agencies.

In the United States, Congress in 2004 gave the Treasury Department the explicit authority to build a cross-border payments database. However, the Treasury has not taken significant pubic action toward that goal since the release of a feasibility study in 2010.[22] Banks are already required to maintain the relevant payment records under existing rules. Reporting them to the Treasury and combining the records in one centralized database would be technically straightforward. According to an official report to Congress, the Treasury has made limited amounts of raw transactional records available to the FBI, which has found them to be a powerful tool for investigating transnational organized crime.[23] Because most of Moldindconbank’s Laundromat activity was in U.S. dollars, the payments passed through New York and been visible to the U.S. government, had an international payments database been in place.

In the EU, the European Central Bank or member states’ central banks or financial supervisors could be tasked with collecting, analyzing, and making available to appropriate agencies all cross-border euro payments data. This information would be particularly useful to a centralized European Union AML institution, should there be a move to create one.[24] In the United Kingdom, the Bank of England, the Financial Conduct Authority, or the Financial Intelligence Unit could do the same for cross-border payments made in pound sterling through London.

Payments in U.S. dollar, euro, and pound sterling together account for a sizeable majority of international wire transfers worldwide, which would give the like-minded authorities of the three jurisdictions a commanding vantage point if they were able to coordinate and collaborate. Australia, Canada, and Norway already operate similar systems at the national level.

In the meantime, until comprehensive databases exist, financial intelligence units, central banks, and AML supervisors should put far more emphasis on monitoring flows between jurisdictions and through particular institutions, which could provide early warning to supervisory examination teams and law enforcement agencies alike.[25]

If Latvia and Cyprus—two of the European jurisdictions historically associated most strongly with non-resident money from Russia—come to be viewed by Russia and CIS financial facilitators as hostile environments, such activity may migrate to smaller European jurisdictions, like Moldova, with less enforcement capacity and weaker rule of law, even if they have not historically been important financial hubs.

The remarkable volume of illicit activity in Moldova, a small country with a small financial sector, demonstrates the risk posed by breakdowns in supervision in even “minor” jurisdictions. MONEYVAL, a Council of Europe body that examines jurisdictions with international AML standards set by the Financial Action Task Force, evaluated Moldova in December 2018 and is set to publish its report this month. It seems likely, given Moldova’s handling of the Laundromat, that the report will be harsh and could lead to “greylisting” of the country, a process that could ultimately trigger enhanced procedures for dealings with its banks.

The most important lesson of the Russian Laundromat—a scheme that relied on Moldindconbank, a bank outside the EU, and Trasta Komercbanka, a bank inside the EU, making payments in dollars through the United States—is that European and U.S. authorities must not play whack-a-mole in fighting such large-scale money laundering. Success will only come from sustained, coordinated, and comprehensive approaches to a sophisticated, multi-jurisdictional threat.

Download the PDF »

[1] “The Russian Laundromat,” OCCRP, August 22, 2014, https://www.reportingproject.net/therussianlaundromat/russian-laundromat.php.

[2] “The Global Laundromat: how did it work and who benefited?”, Luke Harding, The Guardian, March 20, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/20/the-global-laundromat-how-did-it-work-and-who-benefited.

[3] “The Global Laundromat: how did it work and who benefited?”, Luke Harding, The Guardian, March 20, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/20/the-global-laundromat-how-did-it-work-and-who-benefited.

[4] Correspondence between the National Bank of Moldova and Watchdog.MD, a Moldovan anti-corruption NGO.

[6] Copy of a promissory note, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3520227-PROMISSORY-NOTES

[7] “The Russian Laundromat Exposed,” OCCRP, March 20, 2017, https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat-exposed/.

[8] “The Russian Laundromat Superusers Revealed,” Roman Anin, OCCRP, March 20, 2017, https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat-superusers-revealed/.

[9] “Wringing Profits from the Russian Railways,” Olesya Shmagun, OCCRP, April 5,2016, https://www.occrp.org/en/panamapapers/wringing-profits-from-the-russian-railways/.

[10] “#LAUNDROMAT: Two huge scams. One Moldovan businessman,” RISE Moldova, March 2017, https://www.rise.md/english/laundromat-two-huge-scams-one-moldovan-businessman/.

[11] “Project Tenor II Summary Report,” Kroll, Dec. 20, 2017, https://bnm.md/en/content/nbm-published-detailed-summary-second-investigation-report-kroll-and-steptoe-johnson.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Russia: Billion Dollar Laundromat Chief Busted at the Dinner Table,” November 4, 2015, OCCRP, https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/4569-russia-billion-dollar-laundromat-chief-busted-at-the-dinner-table

[14] “The Russian Banks and Putin's Cousin,” OCCRP, August 22, 2014, https://www.reportingproject.net/therussianlaundromat/the-russian-banks-and-putins-cousin.php.

[15] “Russian millions laundered via UK firms, leaked report says,” Luke Harding, The Guardian, February 26, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/26/russian-millions-laundered-via-uk-firms-leaked-report-says.

[16] Allmoldova.com, “Anexele secrete ale Acordului de constituire a AIE” [The secret annexes of the coalition agreement of AIE], Nov 2011, http://www.allmoldova.com/ro/news/vedeti-aici-anexele-secrete-ale-acordului-de-constituire-a-aie

[17] Law no. 90 from 20 May 2010 concerning the state tax, http://lex.justice.md/index.php?action=view&view=doc&lang=1&id=334848.

[18] “Alexandru Tanase appointed judge at Constitutional Court,” Apr 8, 2011, http://www.ipn.md/en/politica/37773.

[19] Adevarul.ro, BNM: “Banca implicată în „mega spălarea“ de bani din Rusia a raportat în permanenţă toate tranzacţiile la CNA” [The bank implicated in the Russian “mega money laundering” was constantly reporting all the transactions to the Anticorruption Center], Apr 2014, https://adevarul.ro/moldova/economie/bnm-banca-implicata-mega-spalarea-bani-rusia-raportat-permanenta-tranzactiile-cna-1_53606afb0d133766a837a080/index.html.

[20] Decision no. 470/16 from 27 May 2014 of the Supreme Council of Magistracy, https://www.csm.md/files/Hotaririle/2014/16/470-16.pdf.

[21] Decision no. 608/25 from 20 Sept 2016 of the Supreme Council of Magistracy, https://www.csm.md/files/Hotaririle/2016/25/608-25.pdf.

[22] “An Effective American Regime to Counter Illicit Finance,” Joshua Kirschenbaum and David Murray, Alliance for Securing Democracy, December 18, 2018, https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/an-effective-american-regime-to-counter-illicit-finance/.

[23] Report to Congress Pursuant to Section 243 of CAATSA, August 6, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/sites/default/files/2018-08/U_CAATSA_243_Report_FINAL.pdf

[24] “A Better European Union Archicteture to Fight Money Laundering,” Bruegel, October 25, 2018, http://bruegel.org/reader/better_EU_architecture_to_fight_money_laundering#.

[25] “Data that could raise alarm bells, such as the share of non-resident deposits or oversized cross-border flows, are collected at national level, often without details of final beneficiaries. No-one checks them at EU level.” Francesco Guarascio: “Explainer: Europe's money laundering scandal”, Reuters, April 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-moneylaundering-explainer/explainer-europes-money-laundering-scandal-idUSKCN1RG1XI. Jesper Berg, the head of Denmark’s FSA, has made similar remarks. See Frances Schwatzkopf, “Hidden Flows and How Danske Bank Revealed Regulatory Gaps”, Bloomberg, December 11, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-10/hidden-flows-and-how-danske-bank-revealed-some-regulatory-gaps.