Dom Twórców: A House in Warsaw for Belarusian Artists

A small team of Belarusians in Poland has been working to support a group of vulnerable people: painters, musicians, actors, theatre performers, and other cultural workers from Belarus who have faced repression and need help or a place for their creativity.

From the Voices Behind Bars to a Song

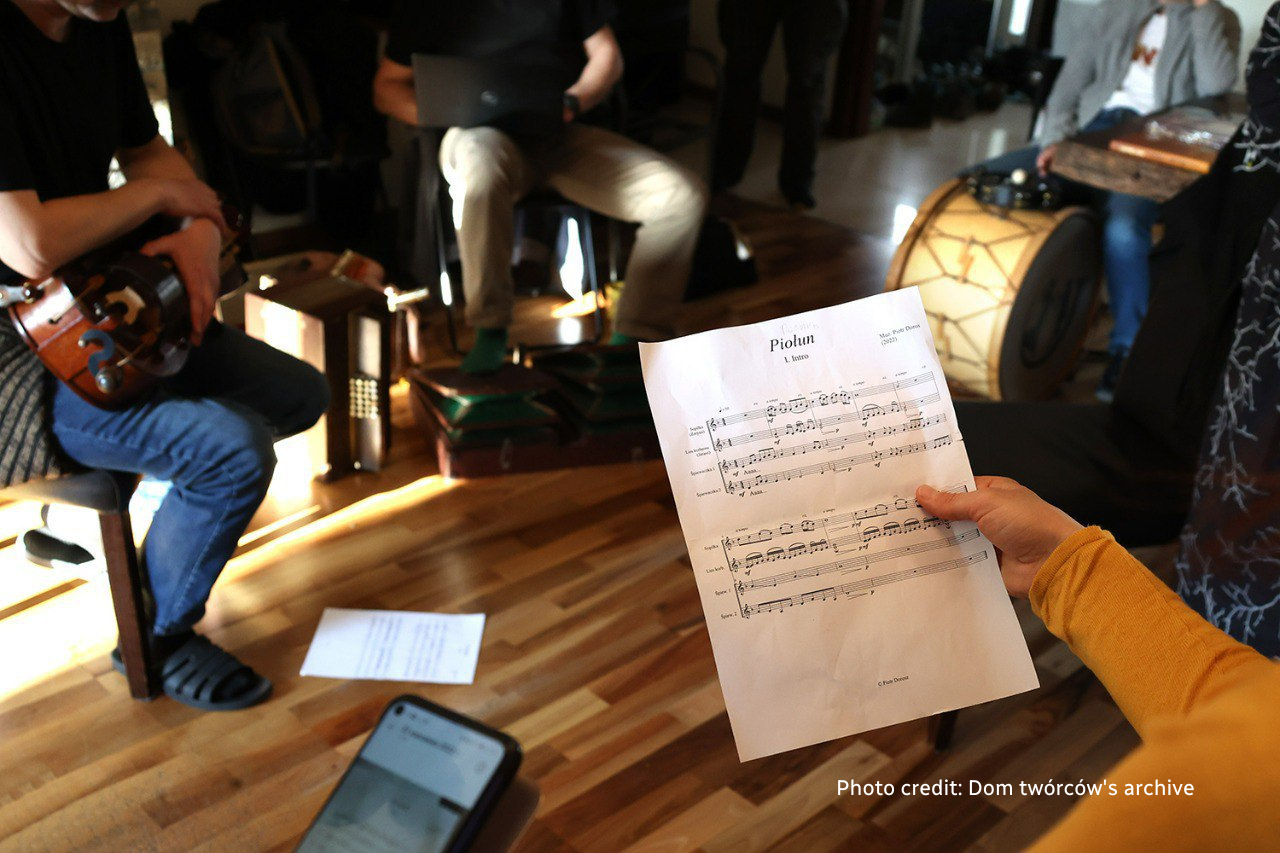

“Some will soar like arrows, some will hide in burrows, but we will become stars, we will become stars” is a lyric from the song Zorami [Stars] that the Belarusian folk band Irdorath wrote while in prison.

In 2021, a court sentenced six members of the band to prison sentences. Its founders, Nadzeya and Uladzimir Kalach, were jailed for two years for “organization or active participation in group actions that grossly violate public order”. The security forces saw criminal misconduct in their “leading a column and involving citizens by playing bagpipes”.

The “bagpipe band” was released in 2023. The musicians moved to Poland where they spent their first months focusing on their psychological and physical recovery. Even now, Nadzeya does not consider their rehabilitation complete.

“You need to spend at least as much time in freedom as you spent in captivity, so nothing is over. Moreover, we find it difficult to accept the phrase ‘ex-political prisoners’. We can only be such when there is none left in Belarus. As long as some are still in prison, we are not free either”, she explains.

The song Zorami expresses the voice of political prisoners that Nadzeya took from jail with her. She wrote the lyrics “while being subjected to forced labor—sewing uniforms for the police”. The song and its accompanying video were the band’s first project after their release.

A Welcome for Hundreds of Belarusian Artists

All the work on the music and video was done at Dom Twórców [House of Creators], where the musicians spent their first months after captivity. In 2021, Belarusian migrants created this facility in Poland so that creatives like them would be able to live, work, meet like-minded people, and receive support. Dom Twórców is a nonprofit organization supported by individuals and foundations such as the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

This place is invaluable for artists, according to Nadzeya. “If it weren’t for Dom Twórców, I have no idea how soon we would have been able to return to music. In the early stages after release, you are helpless, and the stress of the prison experience is compounded by forced migration. It’s a huge blow”, she says. “When you have absolutely nothing, when questions of security, health, and daily life are unresolved. It’s very difficult to overcome this and return back to music, despite the fact that it is our profession”.

Dom Twórców runs a residency program that allows artists to stay and create on its premises at no cost. The first such residency took place in 2021 and was for theatre artists. It resulted in an opera performance, although at that time the nonprofit did not have a space of its own (it only secured one at the end of that year).

The organization had managed to rent premises for artists in Warsaw, says Siarhei Douhushau, its founder-head and a famous folk musician. Over the next two years, the team offered eight residencies and gave support to more than 500 participants.

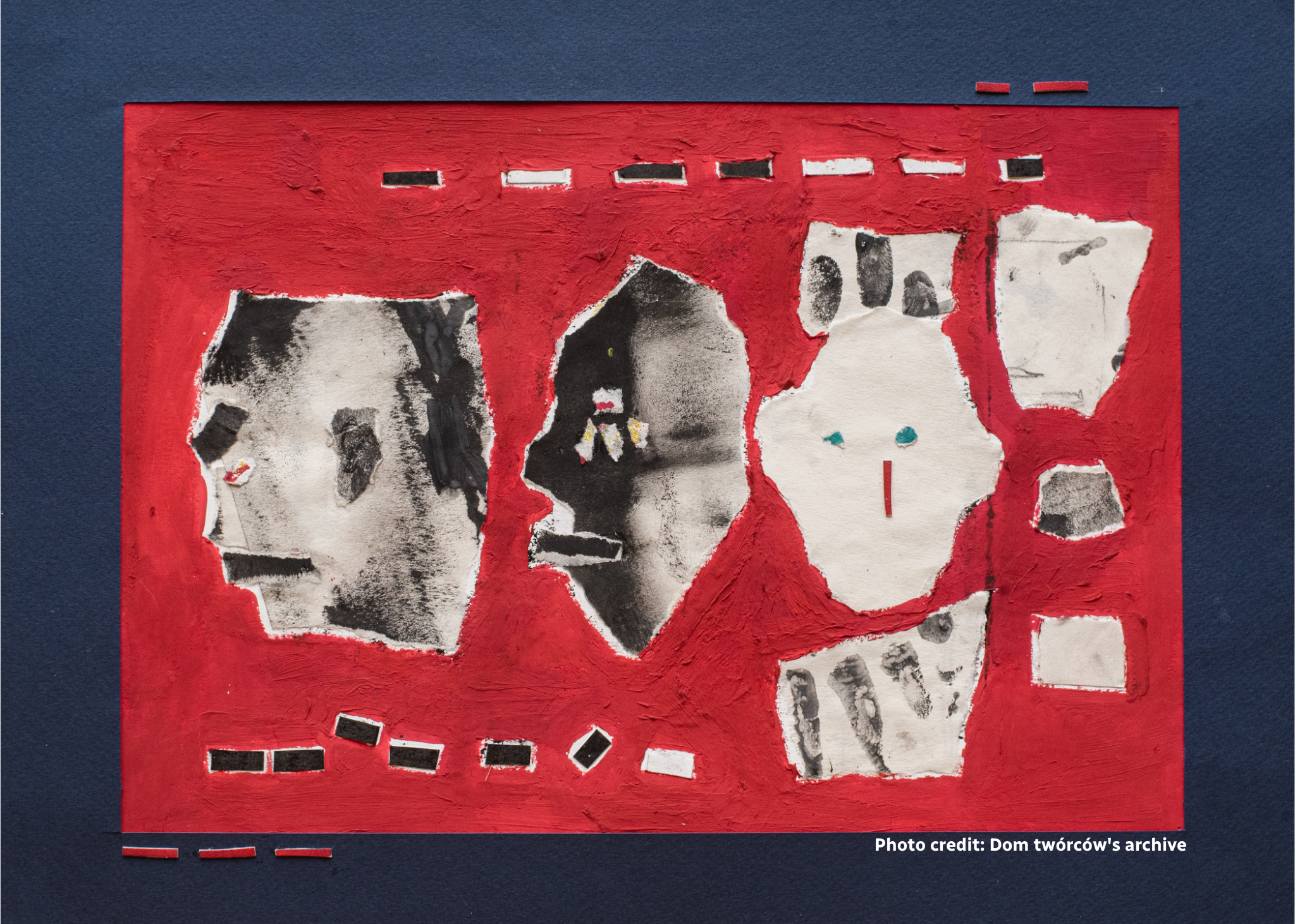

There have also been music and folklore residencies, but the team enjoyed the residencies for visual artists the most. “They resonate with us very much”, says Douhushau, who left Belarus years ago. “For the last residency we invited people from various fields—not only painters but also those who work with ceramics and photography”.

Dom Twórców aims to help artists in their rehabilitation so they can return to their profession and create a new Belarusian culture in emigration. It works with people of any age or gender identity, residing in Poland or any other country, including Belarus. The youngest participant so far was 21 years old and the oldest 80.

The average length of a residency is about a month but requires several months of preparation. The team working on them includes a permanent manager, a house administrator, and a psychologist. For each residency, an expert and curators are invited.

Contacts and Opportunities

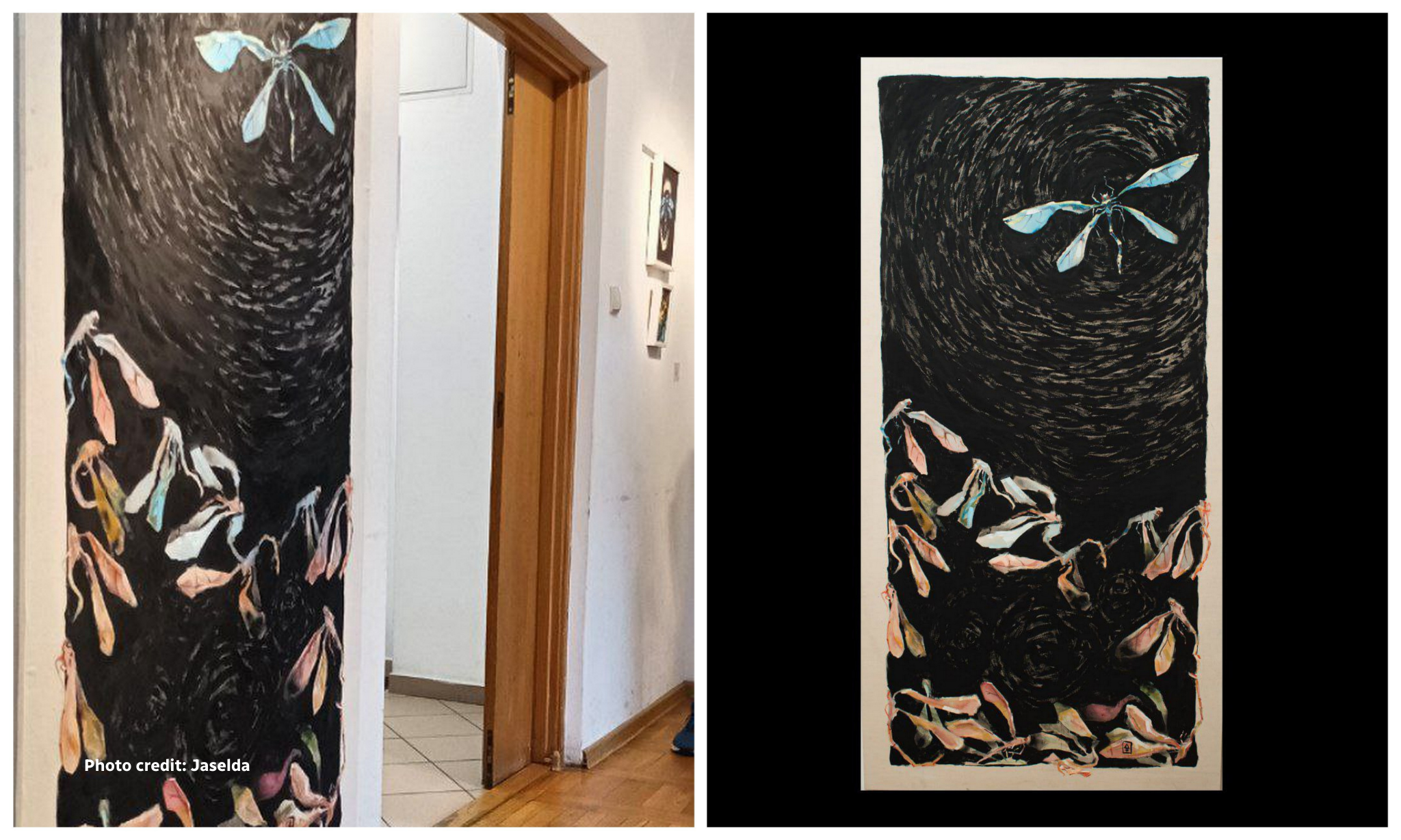

One of the young participants in the Dom Twórców residencies is the artist going by the pseudonym Jaselda, who was forced to leave Belarus and is now a student at the European Humanities University in Lithuania. He paints and practices Malavanka, a traditional Belarusian style of hand-painted textiles. Such art was most popular during the Soviet collectivization period and after the Second World War.

“I was impressed that such a residency even exists. It’s a place where people from different locations can gather and work in cooperation, because it’s difficult to survive in our world alone. The value of this place is both in the contacts you make and in the fact that they tell us about various opportunities and initiatives”, Jaselda says.

There are meetings with renowned Polish artists, visits to the Academy of Fine Arts, sessions with performers, and field trips. After these, the residents can get invited to workshops or to work, Douhushau explains.

Jaselda adds that it is very important for an artist to be part of a community, especially when they are right at the beginning of their journey. “I met people sharing the same values as myself and realized that my work is important and needs to be progressed. I was lucky to work with fantastic people, and the main result of our residency was an exhibition and a collection of works dedicated to social problems, as well as to the issues of emigration and the prohibition of creativity in Belarus”.

A New Working Context

Dom Twórców does not just aim to provide artists with space, as other creative residencies do—it works help them cope with challenging work conditions in Belarus and in emigration.

“In Belarus, it’s not easy to get help from the government. Although usually what you want first is not even help but simply to be left alone. I remember that, when I organized concerts, there was never any guarantee that a concert wouldn’t be banned”, says Douhushau. “The most significant obstacles were in all cities besides Minsk, and the smaller the city was, the greater were the obstacles”.

Jaselda adds: “You can be considered unreliable by the state and get blacklisted. In that case your exhibitions would be banned, you would have troubles receiving grant funding. But the state would do it quietly, it would look like an unofficial restriction”. He believes that this situation puts artists in a grey zone between legality and illegality.

After leaving Belarus, Jaselda found himself in a more nurturing environment, albeit a completely foreign one. For him, creating in emigration is less complicated as there is more freedom, but it also means working in a foreign context and for a foreign audience.

In the long run, Dom Twórców aims to develop an international dimension to its residencies program by inviting experts from a variety of countries.